An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Factors related to Internet and game addiction among adolescents: A scoping review

Siripattra juthamanee, joko gunawan.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author: Siripattra Juthamanee, MNS, RN , Faculty of Nursing, Rajamangala University of Technology Thanyaburi. 39 Moo 1, Klong 6, Khlong Luang Pathum Thani 12110, Thailand. Email: [email protected]

Cite this article as: Juthamanee, S., & Gunawan, J. (2021). Factors related to Internet and game addiction among adolescents: A scoping review. Belitung Nursing Journal, 7 (2), 62-71. https://doi.org/10.33546/bnj.1192

Received 2020 Sep 1; Revised 2020 Oct 23; Accepted 2021 Mar 18; Collection date 2021.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially as long as the original work is properly cited. The new creations are not necessarily licensed under the identical terms.

Understanding factors influencing Internet and game addiction in children and adolescents is very important to prevent negative consequences; however, the existing factors in the literature remain inconclusive.

This study aims to systematically map the existing literature of factors related to Internet and game addiction in adolescents.

A scoping review was completed using three databases - Science Direct, PROQUEST Dissertations and Theses, and Google Scholar, which covered the years between 2009 to July 2020. Quality appraisal and data extraction were presented. A content analysis was used to synthesize the results.

Ultimately, 62 studies met inclusion criteria. There were 82 associated factors identified and grouped into 11 categories, including (1) socio-demographic characteristics, (2) parental and family factors, (3) device ownership, Internet access and location, social media, and the game itself, (4) personality/traits, psychopathology factors, self-efficacy, (5) education and school factors, (6) perceived enjoyment, (7) perceived benefits, (8) health-compromising behaviors, (9) peers/friends relationships and supports, (10) life dissatisfaction and stress, and (11) cybersafety.

Internet and game addiction among adolescents are multifactorial. Nurses should consider the factors identified in this study to provide strategies to prevent and reduce addiction in adolescents.

Keywords: adolescent, addictive behavior, Internet, gaming, influencing factors, nursing

Internet addiction has become a significant concern in the public and scientific communities today. Although the Internet has become an indispensable tool in the adolescent population for entertainment, communication, information, academic search, and social recognition (Frangos et al., 2011 ), there is strong evidence that those who addict to the Internet has a negative influence on their lives, such as sleep, academic performance, and relationship with others (Milani et al., 2018 ). It is also similar to individuals who enjoy games. Although games have become a major leisure activity for releasing stress, heavy users tend to be isolated and lack confidence and social skills (Herodotou et al., 2012 ).

There have been a wide variety of terms examining the Internet and gaming addiction, such as “Internet gaming disorder”, “problematic online gamers”, “problem video game use”, “problematic Internet use”, “Internet addictive behavior”, “digital game addiction”, “excessive use of the Internet and online gaming”, “online game addiction”, “persistence of Internet addiction”, “smartphone addiction”, “unregulated Internet use”, “pathological Internet use”, and “overuse of Internet”. In this study, we use the terms “Internet and game addiction” for the sake of consistency.

Although the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) has described game addiction (American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ), it is still a lack of evidence to consider the condition as a unique mental disorder. In addition, this condition is only limited to gaming, not including the general use of the Internet, social media, smartphones, and online gaming. Therefore, it has led to a degree of ambiguity in understanding the concept of Internet and gaming addiction, which needs further clarification. However, in this review, we did not limit our exploration to gaming only. All terms related to the Internet, social media, and online or offline gaming, with the use of mobile phones, computers, or laptops, were included because all of them were mainly about non-substance addiction, which has a lot in common with substance addictions.

Despite multiple constructs of addiction in the literature, in this study, addiction is defined based on the following four points, including 1) excessive use, or increasing time and frequency, 2) persistent, maladaptive preoccupation, and craving, or feeling an irresistible urge to play computer games, 3) having characteristics of withdrawal behaviors, tolerant behavior, loss of control, negative repercussions, 4) having negative effects on academic or work performance, interpersonal relationships, financial or physical problems, and gaining or losing weight (Chen et al., 2015 ; Hu et al., 2017 ; Milani et al., 2018 ; Müller et al., 2015 ). If there are no negative consequences, it will not be considered an addiction because it can be an adaptive user instead of a maladaptive user.

It is undebatable that Internet and gaming addiction has tremendous impacts on adolescents. Therefore, its related factors warrant further exploration. Although previous studies have found several factors influencing Internet and gaming addiction, such as individual characteristics (Rho et al., 2016 ), parenting behavior (Kwak et al., 2018 ), education (Karaca et al., 2020 ), and other factors. However, these factors are somewhat inconclusive. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore the factors related to Internet and game addiction in adolescents. The research question in this review was, “what are the factors associated with Internet and game addiction in adolescents?” This study is expected to help pediatric nurses or mental health nurses to reduce addiction among adolescents.

Search Methods

Three databases used in this study, including Science Direct, ProQuest, and Google Scholars. The key words include “Internet AND game AND addiction OR addictive behavior OR behavior AND antecedents OR factors AND consequences AND adolescents AND young adolescents AND early adolescents AND children.” The reason we included children due to the fact that many addictions adolescents start during the children period. The search strategy was just limited to ten years, ranged from January 2009 - July 2020 to get the current literature.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria of the article were all research studies with qualitative and quantitative approaches, full-text articles and theses or dissertations, and available in English. The exclusion criteria were review articles, editorials, letters to editors, magazines, or gray literature.

The screening of the article was done by both authors, which included the title, abstract, and full-text. All articles that meet inclusion criteria were included.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted using a table, which consists of the author’s name, year, country, objective, theoretical framework, attributes/dimensions, antecedents, instru-ments, and study design.

Quality Appraisal

To ensure the quality of each study, a quality appraisal tool adapted from previous studies (Gunawan et al., 2018 ; Keyko et al., 2016 ) was used for the correlational study. Each study was categorized as high (10-14), moderate (5-9), and low (0-4) quality. For qualitative studies, the Critical Skills Appraisal Program (CSAP) was used (Casp, 2010 ). Areas for assessments were research design, measu-rement, sampling, data collection, ethical issues, and data analysis.

Data Analysis

Content analysis was used to synthesize the results from both the quantitative and qualitative studies (Grove et al., 2012 ). This content analysis is specifically to merge the factors into categories.

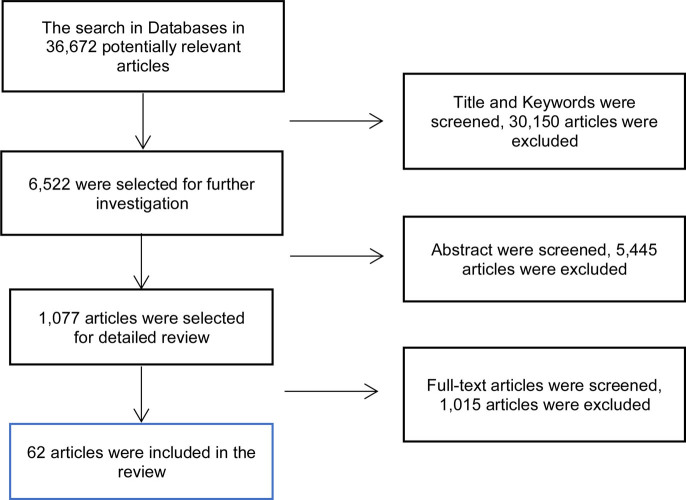

Search Results

There were 36,672 potential articles identified from the initial search ( Table 1 ). In the stage of title screening, we removed 30,150 articles due to unrelated topics with Internet and game addiction, and 6,522 articles were left for further evaluation. In the stage of abstract screening, 5,445 articles were excluded due to inadequate in terms of inclusion criteria, and 1,077 articles were retained for further exploration. Ultimately, 62 articles were included (see Figure 1 ). The characteristics of the included studies can be seen in the supplementary file .

Database Searching

The Review Process based PRISMA Flow Chart

Quality Assessment

Majorities of the studies employed a correlational cross-sectional study design. Six studies used a longitudinal design, and one study was qualitative. Among 62 studies, only 22 studies used probability sampling, 11 studies used non-probability sampling, and 29 studies did not report sampling methods. In the quality assessment of all studies, 52 studies were at medium level and ten studies at a high level. The majority of the studies used three scales for measuring Internet and game addiction as developed by Lemmens et al. ( 2009 ), Chen et al. ( 2003 ), and Young ( 1998 ). There were various countries identified in the studies, including Serbia, Germany, Greece, Iceland, The Netherland, Poland, Romania, Spain, Geneva, Taiwan, Australia, Turkey, United Kingdom, China, Hong Kong, Italy, Norway, Malaysia, Mongolia, Korea, Czech Republic, France, Singapore, Iran, Thailand, India, United States, and Nigeria (see Supplementary file ).

Analytical Findings

A total of 82 factors were identified and synthesized into 11 categories, including 1) socio-demographic charact-eristics, 2) parent and family factors, 3) devise ownership, Internet access, and location, social media, and the game itself, 4) personality/traits, psychopathology factors, self-efficacy, 5) education and school factors, 6) perceived enjoyment, 7) perceived benefits, 8) health-compromising behaviors, 9) peers/friends relationships and supports, 10) life dissatisfaction and stress, and 11) cybersafety (see Table 2 ).

Factors related to the game or Internet addiction

There were eleven groups of factors that emerged in the findings of this study as following.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

There were eight factors of the Internet and game addiction according to socio-demographic characteristics: (1) Age , there were seven studies have provided the significant correlation between age and Internet and game addiction (Bianchini et al., 2017 ; Hyun et al., 2015 ; Karaca et al., 2020 ; Lim & Nam, 2018 ; Müller et al., 2015 ; Rehbein et al., 2010 ; Tsitsika et al., 2014 ). Karaca et al. ( 2020 ) revealed that Internet and game addiction was significantly in the older age of adolescents than in the younger age group. Rehbein et al. ( 2010 ) found that 15-year-old children were shown the specific risk factors of addiction at the age of ten years; (2) Gender , 13 studies discussed the linkage between gender and Internet and game addiction, which predominantly specific to males (Chen et al., 2015 ; Choo et al., 2015 ; Dhir et al., 2015 ; Frangos et al., 2011 ; Lin et al., 2011 ; Müller et al., 2015 ; Samarein et al., 2013 ; Sul, 2015 ; Toker & Baturay, 2016 ; Walther et al., 2012 ) than females (Lee et al., 2017 ). Hyun et al. ( 2015 ); Spilkova et al. ( 2017 ) stated that females are more prone to online communication and social media use, while males are more likely to online gaming; (3) Residence type , Frangos et al. ( 2011 ) revealed that those who were not staying with parents are highly associated with Internet addiction; (4) Individual marital status , Rho et al. ( 2016 ) found that those who are single are more prone to Internet addiction than those who are married; (5) Parental marital status , Frangos et al. ( 2011 ); Müller et al. ( 2015 ) revealed that those who have divorced parental condition are more addicted to Internet or game online; (6) Parental education , Wu, Zhang, et al. ( 2016 ) said mother’s and father’s education significantly correlate with Internet addiction. Karaca et al. ( 2020 ) found that those having parents who completed high school or a higher education level are more likely to be addicted to online game addiction. Conversely, Müller et al. ( 2015 ) revealed that those who have a mother with no formal education (not father’s education) are more addicted to Internet gaming addiction; (7) Parental employment status , Karaca et al. ( 2020 ) found that a mother who is employed is considered a factor of online game addiction in adolescents; (8) Parental economic/income status , Toker and Baturay ( 2016 ) and Wu, Zhang, et al. ( 2016 ) found that socioeconomic status or per capita annual household income is significantly related to the addiction rate. Walther et al. ( 2012 ) and Wu, Zhang, et al. ( 2016 ) revealed that high economic status tends to have problematic computer gaming in adolescents.

Parent and Family Factors

We discussed parent and family factors separately. For parental factors, there were six factors associated with the Internet and game addiction: (1) Parent-child relationship, Choo et al. ( 2015 ) revealed that parent-child relationship is an important predictor of the Internet or game addiction although King and Delfabbro ( 2017 ) stated that parent-child relationships have a weak correlation with Internet addiction; (2) Parental monitor/control, Bonnaire and Phan ( 2017 ); Wu, Zhang, et al. ( 2016 ) found that parental monitoring is correlated with Internet and game addiction. Walther et al. ( 2012 ) emphasize that lower parental monitoring is consistently associated with addictive behaviors. But, Ding et al. ( 2017 ) explained it differently that deviant peer affiliation is partially mediated the correlation between parental monitoring and Internet addiction, while Li et al. ( 2014 ) said that Internet addiction was explained positively by parents’ negative control; (3) Parental conflict, Bonnaire and Phan ( 2017 ) found that parental conflict is significantly related to Internet gaming addiction; (4) Parent positive support , Li et al. ( 2014 ) found that parents’ positive support was negatively correlated with Internet addiction; (5) Parental neglect, Kwak et al. ( 2018 ) found that smartphone addiction was significantly influenced by parental neglect; and (6) Parental knowledge, Tian et al. ( 2019 ) found that those with low parental knowledge are more addicted than those with high parental knowledge.

For family factors, the studies indicated that those with poorer family relationships, multicultural and dual-income families, and poor family function are likely to be addicted more to the Internet and game addiction (Bonnaire & Phan, 2017 ; Choi & Yoo, 2015 ; Sul, 2015 ). In addition, Sul ( 2015 ) revealed that family leisure is one factor that correlates with Internet game addiction, in which the adolescents could join the family to enjoy the environment.

Device Ownership, Internet Access, Location, Social Media & Game Itself

According to Smith et al. ( 2015 ) and Toker and Baturay ( 2016 ), device and computer ownership are related to game addiction. Additionally, Frangos et al. ( 2011 ) said that subscription to the Internet is associated with Internet addiction, while Wu, Zhang, et al. ( 2016 ) found Internet café where adolescents could access the Internet is related to addiction.

Of course, without online and computer games or social media applications, the addictive behavior will not occur (Kuss et al., 2013 ; Toker & Baturay, 2016 ; Tsitsika et al., 2014 ). Müller et al. ( 2015 ) said that all game genres are related to Internet gaming disorder. Lee and Kim ( 2017 ) found that simulation, RPG, and casual games were positively correlated with addictive behavior. In addition, structural characteristics of the game influence the level of addiction (Hull et al., 2013 ), while Rho et al. ( 2016 ) revealed that gaming cost is also an important factor of the Internet and game addiction. Besides, Smith et al. ( 2015 ) found that bedroom location is associated with video-game play, which leads to addiction.

Personality Factors/ Traits, Psychopathology Factors, and Self-Efficacy

There were 15 personality factors or traits that are related to Internet and game addiction, including low self-esteem (Billieux et al., 2015 ; Charoenwanit & Sumneangsanor, 2014 ; Hyun et al., 2015 ; Walther et al., 2012 ), high impulsivity and sensation seeking (Walther et al., 2012 ), aggression/ rule breaking behavior/ irritability (Tsitsika et al., 2014 ; Walther et al., 2012 ), extraversion (Andreassen et al., 2013 ; Kuss et al., 2013 ; Samarein et al., 2013 ), introversion (Torres-Rodríguez et al., 2018 ), neuroticism (anxiety, anger, depression, loneliness, hostility, emotional stability) (Andreassen et al., 2013 ; Dong et al., 2013 ; Hyun et al., 2015 ; Jeong et al., 2015 ; Kuss et al., 2013 ; Mehroof & Griffiths, 2010 ; Samarein et al., 2013 ; Tsitsika et al., 2014 ; Vukosavljevic-Gvozden et al., 2015 ; Walther et al., 2012 ) (Chang et al., 2014 ; Hyun et al., 2015 ; Jeong et al., 2015 ; Laconi et al., 2017 ; Lin et al., 2011 ; Moslehpour & Batjargal, 2013 ; Tsitsika et al., 2014 ; Vukosavljevic-Gvozden et al., 2015 ; Walther et al., 2012 ), conscientiousness (Andreassen et al., 2013 ; Kuss et al., 2013 ; Samarein et al., 2013 ; Stavropoulos et al., 2016 ), agreeableness (Andreassen et al., 2013 ; Kuss et al., 2013 ; Samarein et al., 2013 ; Walther et al., 2012 ), resourcefulness (Kuss et al., 2013 ), openness to experience (Andreassen et al., 2013 ), psychoticism/ socialization (Dong et al., 2013 ), low self-control (Li et al., 2014 ), and effortful control (Ding et al., 2017 ), IQ (Hyun et al., 2015 ).

Specifically, Andreassen et al. ( 2013 ) found that extraversion is positively associated with Internet and game addiction, while Kuss et al. ( 2013 ); Samarein et al. ( 2013 ) found that extraversion is negatively correlated with the addiction. Neuroticism (Andreassen et al., 2013 ; Samarein et al., 2013 ) and resourcefulness (Kuss et al., 2013 ) are positively related to addiction, while conscientiousness (Andreassen et al., 2013 ; Kuss et al., 2013 ; Samarein et al., 2013 ; Stavropoulos et al., 2016 ), agreeableness (Andreassen et al., 2013 ; Kuss et al., 2013 ; Samarein et al., 2013 ), and openness to experience (Andreassen et al., 2013 ), are negatively correlated to addiction. For effortful control, Ding et al. ( 2017 ) found that the correlation between parental monitoring and deviant peer affiliation is moderated by effortful control, which in turn increases Internet addiction.

Psychopathology Factor

There were direct and indirect relationships between psychopathology factors and the Internet and game addiction. Vukosavljevic-Gvozden et al. ( 2015 ) found that somatization, phobic anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, anxiety, paranoid ideation, hostility, and psychoticism are mediating factors of game addiction. In comparison, Torres-Rodríguez et al. ( 2018 ) found that obsessive–compulsive, interpersonal sensibility, paranoia, self-devaluation, and borderline are direct factors of Internet and game addiction. Lee et al. ( 2017 ) also found that ubiquitous trait is directly associated with addiction. The other direct factors of addiction include ADHD (Chen et al., 2015 ; Hyun et al., 2015 ; Walther et al., 2012 ), autistics traits (Chen et al., 2015 ), impaired social adjustment (Chen et al., 2015 ), attention problem (Peeters et al., 2018 ), insecure attachment (Lin et al., 2011 ), perseverative errors (Hyun et al., 2015 ), and lie (Dong et al., 2013 ). For anxiety, Mehroof and Griffiths ( 2010 ) found that online gaming addiction was significantly associated with trait and state anxiety. While phobic anxiety, according to Vukosavljevic-Gvozden et al. ( 2015 ), is considered a mediator of game addiction.

In regards to self-efficacy, Jeong et al. ( 2015 ) found that game addiction is negatively influenced by general self-efficacy but positively affected by game self-efficacy. Lin et al. ( 2011 ) also found that lower refusal self-efficacy of Internet use increases addiction, and Walther et al. ( 2012 ) revealed that social self-efficacy is related to game addiction.

Education & School Factors

There are three education and school factors: 1) academic performance , Chen et al. ( 2015 ) and Lin et al. ( 2011 ) found that Internet addiction was significantly correlated with poor academic performance. Wu, Zhang, et al. ( 2016 ) emphasized that the adolescents who had very poor academic performance were 2.4 times were more likely to report Internet addiction than those who had first-class academic performance; 2) school bonding or relationship with teachers , Chang et al. ( 2014 ) found that there was an increase in online activities for those with lower school bonding in grade 10. Similar to Lee and Kim ( 2017 ), who revealed that the respondents with less satisfaction with their relationships with teachers were more likely to be game addicts; 3) school well-being , Rehbein et al. ( 2010 ) revealed that students with low experienced school well-being are related to game addiction.

Perceived Enjoyment

Perceived enjoyment is considered a direct factor of addiction, which consist of the feeling of excitement, relief from negative emotion, passing time (Billieux et al., 2015 ), entertainment (Moslehpour & Batjargal, 2013 ), flow (Hull et al., 2013 ; Sun et al., 2015 ), leisure environment (Lee & Kim, 2017 ), gratification (Dhir et al., 2015 ; Hull et al., 2013 ), perceived visibility and enjoyment (Sun et al., 2015 ), and preoccupation (Lee et al., 2017 ). In terms of flow, Sun et al. ( 2015 ) added that flow directly affects addiction but also acted as mediating variable of perceived visibility and enjoyment.

Perceived Benefits

Adiele and Olatokun ( 2014 ) found that the benefits or extrinsic factors of Internet addiction were for communication on important matters, making money (especially amongst females), getting-sex oriented materials. Billieux et al. ( 2015 ); Kim and Kim ( 2017 ); Moslehpour and Batjargal ( 2013 ); Porter et al. ( 2010 ) revealed that making friends is the reason for addiction. Additionally, Lee et al. ( 2017 ) stated that the Internet was used for learning, while Kim and Kim ( 2017 ) found that online self-identity is also one of the reasons for addiction.

Health-Compromising Behaviors

The health-compromising behaviors that are associated with the Internet and game addiction are likely related to smoking (Chang et al., 2014 ; Frangos et al., 2011 ; Spilkova et al., 2017 ; Toker & Baturay, 2016 ), drinking alcohol (Frangos et al., 2011 ; Spilkova et al., 2017 ), and using the drug (Frangos et al., 2011 ). Interestingly, Frangos et al. ( 2011 ) also said that drinking coffee is one factor of addiction.

Peers/Friends Relationships and Supports

The relationships between peer and support and Internet and game addiction have been discussed in four studies (Kwak et al., 2018 ; Lee & Kim, 2017 ; Wu, Ko, et al., 2016 ; Wu, Zhang, et al., 2016 ). Kwak et al. ( 2018 ) said that smartphone addiction was negatively influenced by the relational maladjustment with peers, while Wu, Ko, et al. ( 2016 ) stated that peer influences (invitation to play, frequency of Internet game use, and positive attitudes toward Internet gaming) were positively associated with Internet gaming addiction. Peer influence was also mediated through the positive outcome expectancy of Internet gaming. According to Ding et al. ( 2017 ), peer affiliation is considered a mediating variable of the relationship between Internet addiction and perceived parental monitoring. Rho et al. ( 2016 ) stated that Internet gaming community meeting attendance is also the factor of addiction.

Life Dissatisfaction & Stress

Moslehpour and Batjargal ( 2013 ) found that stress is the factor that influences Internet addiction among adolescents, while Peeters et al. ( 2018 ) found that life dissatisfaction was the predictor of Internet addiction.

Cybersafety

Only one study discusses the relationship between cybersafety and game addiction, as indicated by Smith et al. ( 2015 ). This is, however, considered as an important factor that parents should discuss cyber safety as the protective factor of Internet or game addiction.

Summary of the Findings

The strong evidence of the number of studies in our review can be compared with a large volume of literature on the Internet and gaming addiction among adolescents. To understand the issues related to addiction, it is necessary to understand how factors are correlated with another from 11 categories retrieved by this review. The majority of the factors are found to be directly associated, while some are mediated by the others, specifically between personality/traits, psychopathology factors, and addiction.

However, if all those factors are seen from internal and external categories, socio-demographic characteristics, personality/traits, psychopathology factors, self-efficacy, perceived enjoyment, perceived benefits, health-compromising behaviors, life dissatisfaction, and stress can be considered internal factors. While parent and family factors, devise ownership, Internet access and location, social media, and the game itself, education and school factors, peers or friends’ relationships and supports, and cybersafety are considered external factors.

This study provides a comprehensive review of the factors associated with the Internet and gaming addiction among adolescents. However, those factors need further validation and determine how they are related to each other. This study’s limitation may include that the Internet and gaming addiction in some studies were not well defined. Hence, it is possible that some important articles might not be included in this study. In addition, if the Internet and gaming addiction is considered different and in terms of the target population between children and adolescents, then the findings of this study are limited. However, this study provides the implication for pediatric nurses or community nurses in dealing with adolescents with Internet and gaming addiction. The factors identified in this study can be used as basic information to provide intervention to decrease addiction levels.

Understanding the factors related to Internet and game addiction can help the development of adolescents. This systematic review shows that factors related to the Internet and gaming addiction are multifactorial and not well understood. There were 82 factors identified and categorized into 11 groups: (1) socio-demographic characteristics, (2) parent and family factors, (3) devise ownership, internet access, and location, social media, and the game itself, (4) personality/traits, psychopathology factors, self-efficacy, (5) education and school factors, (6) perceived enjoyment, (7) perceived benefits, (8) health-compromising behaviors, (9) peers/friends relationships and supports, (10) life dissatisfaction and stress, and (11) cybersafety. Further research is needed to validate the factors and clarify the linkage among factors.

Supplementary Material

Declaration of conflicting interest.

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors contributed equally to conceptualization, methodology, validation, literature review, data collection, analysis, data interpretation, and writing and editing of the manuscript. Both authors agreed with the final version of the article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information file ).

Authors Biographies

Siripattra Juthamanee, MNS, RN is a Lecturer at the Faculty of Nursing, Rajamangala University of Technology Thanyaburi, Thailand.

Joko Gunawan, PhD, RN is a Director of Belitung Raya Foundation, Bangka Belitung, Indonesia.

- Adiele, I., & Olatokun, W. (2014). Prevalence and determinants of Internet addiction among adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior , 31, 100-110. 10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.028 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- American Psychiatric Association . (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. [ Google Scholar ]

- Andreassen, C. S., Griffiths, M. D., Gjertsen, S. R., Krossbakken, E., Kvam, S., & Pallesen, S. (2013). The relationships between behavioral addictions and the five-factor model of personality. Journal of Behavioral Addictions , 2(2), 90-99. 10.1556/jba.2.2013.003 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bianchini, V., Cecilia, M. R., Roncone, R., & Cofini, V. (2017). Prevalence and factors associated with problematic Internet use: An Italian survey among L’Aquila students. Rivista di Psichiatria , 52(2), 90-93. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Billieux, J., Thorens, G., Khazaal, Y., Zullino, D., Achab, S., & Van der Linden, M. (2015). Problematic involvement in online games: A cluster analytic approach. Computers in Human Behavior , 43, 242-250. 10.1016/j.chb.2014.10.055 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bonnaire, C., & Phan, O. (2017). Relationships between parental attitudes, family functioning and Internet gaming disorder in adolescents attending school. Psychiatry Research , 255, 104-110. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.030 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carli, V., Durkee, T., Wasserman, D., Hadlaczky, G., Despalins, R., Kramarz, E., … Brunner, R. (2013). The association between pathological Internet use and comorbid psychopathology: A systematic review. Psychopathology , 46(1), 1-13. 10.1159/000337971 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- CASP . (2010). 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research . Retrieved from http://www.caspinternational.org/mod_product/uploadsCASP%20Qualitative%20Research%20Checklist%2031.05.13.pdf .

- Chang, F.-C., Chiu, C.-H., Lee, C.-M., Chen, P.-H., & Miao, N.-F. (2014). Predictors of the initiation and persistence of Internet addiction among adolescents in Taiwan. Addictive Behaviors , 39(10), 1434-1440. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.05.010 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Charoenwanit, S., & Sumneangsanor, T. (2014). Predictors of game addiction in children and adolescents. Thammasat Review , 17(1), 150-166. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen, S.-H., Weng, L.-J., Su, Y.-J., Wu, H.-M., & Yang, P.-F. (2003). Development of a Chinese Internet addiction scale and its psychometric study. Chinese Journal of Psychology . [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen, Y.-L., Chen, S.-H., & Gau, S. S.-F. (2015). ADHD and autistic traits, family function, parenting style, and social adjustment for Internet addiction among children and adolescents in Taiwan: A longitudinal study. Research in Developmental Disabilities , 39, 20-31. 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.12.025 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Choi, H. J., & Yoo, J. H. (2015). A study on the relationship between self-esteem, social support, smartphone dependency, internet game dependency of college students. Journal of East-West Nursing Research , 21(1), 78-84. 10.14370/jewnr.2015.21.1.78 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Choo, H., Sim, T., Liau, A. K. F., Gentile, D. A., & Khoo, A. (2015). Parental influences on pathological symptoms of video-gaming among children and adolescents: A prospective study. Journal of Child and Family Studies , 24(5), 1429-1441. 10.1007/s10826-014-9949-9 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dhir, A., Chen, S., & Nieminen, M. (2015). Predicting adolescent Internet addiction: The roles of demographics, technology accessibility, unwillingness to communicate and sought Internet gratifications. Computers in Human Behavior , 51, 24-33. 10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.056 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ding, Q., Li, D., Zhou, Y., Dong, H., & Luo, J. (2017). Perceived parental monitoring and adolescent Internet addiction: A moderated mediation model. Addictive Behaviors , 74, 48-54. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.05.033 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dong, G., Wang, J., Yang, X., & Zhou, H. (2013). Risk personality traits of Internet addiction: A longitudinal study of Internet-addicted Chinese university students. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry , 5(4), 316-321. 10.1111/j.1758-5872.2012.00185.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frangos, C. C., Frangos, C. C., & Sotiropoulos, I. (2011). Problematic internet use among Greek university students: An ordinal logistic regression with risk factors of negative psychological beliefs, pornographic sites, and online games. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking , 14(1-2), 51-58. 10.1089/cyber.2009.0306 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frisch, N. C., & Frisch, L. E. (2006). Psychiatric mental health nursing . Canada: Thomson Delmar Learning. [ Google Scholar ]

- Grove, S. K., Burns, N., & Gray, J. (2012). The practice of nursing research: Appraisal, synthesis, and generation of evidence . Amsterdam: Elsevier Health Sciences. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gunawan, J., Aungsuroch, Y., & Fisher, M. L. (2018). Factors contributing to managerial competence of first-line nurse managers: A systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Practice , 24(1), e12611. 10.1111/ijn.12611 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Herodotou, C., Winters, N., & Kambouri, M. (2012). A motivationally oriented approach to understanding game appropriation. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction , 28(1), 34-47. 10.1080/10447318.2011.566108 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hu, J., Zhen, S., Yu, C., Zhang, Q., & Zhang, W. (2017). Sensation seeking and online gaming addiction in adolescents: A moderated mediation model of positive affective associations and impulsivity. Frontiers in Psychology , 8, 699. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00699 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hull, D. C., Williams, G. A., & Griffiths, M. D. (2013). Video game characteristics, happiness and flow as predictors of addiction among video game players: A pilot study. Journal of Behavioral Addictions , 2(3), 145-152. 10.1556/jba.2.2013.005 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hyun, G. J., Han, D. H., Lee, Y. S., Kang, K. D., Yoo, S. K., Chung, U.-S., & Renshaw, P. F. (2015). Risk factors associated with online game addiction: A hierarchical model. Computers in Human Behavior , 48, 706-713. 10.1016/j.chb.2015.02.008 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jeong, E. J., Lee, H. R., & Yoo, J. H. (2015). Addictive use due to personality: focused on big five personality traits and game addiction. International Journal of Social, Behavioral, Educational, Economic, Business and Industrial Engineering , 9(6), 1995-1999. [ Google Scholar ]

- Karaca, S., Karakoc, A., Gurkan, O. C., Onan, N., & Barlas, G. U. (2020). Investigation of the online game addiction level, sociodemographic characteristics and social anxiety as risk factors for online game addiction in middle school students. Community Mental Health Journal , 1-9. 10.1007/s10597-019-00544-z [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Keyko, K., Cummings, G. G., Yonge, O., & Wong, C. A. (2016). Work engagement in professional nursing practice: A systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies , 61, 142-164. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.06.003 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kim, Y.-Y., & Kim, M.-H. (2017). The impact of social factors on excessive online game usage, moderated by online self-identity. Cluster Computing , 20(1), 569-582. 10.1007/s10586-017-0747-1 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- King, D. L., & Delfabbro, P. H. (2017). Features of parent-child relationships in adolescents with Internet Gaming Disorder. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction , 15(6), 1270-1283. 10.1007/s11469-016-9699-6 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ko, C.-H., Yen, J.-Y., Chen, C.-C., Chen, S.-H., & Yen, C.-F. (2005). Gender differences and related factors affecting online gaming addiction among Taiwanese adolescents. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease , 193(4), 273-277. 10.1097/01.nmd.0000158373.85150.57 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kuss, D. J., Van Rooij, A. J., Shorter, G. W., Griffiths, M. D., & van de Mheen, D. (2013). Internet addiction in adolescents: Prevalence and risk factors. Computers in Human Behavior , 29(5), 1987-1996. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kwak, J. Y., Kim, J. Y., & Yoon, Y. W. (2018). Effect of parental neglect on smartphone addiction in adolescents in South Korea. Child Abuse & Neglect , 77, 75-84. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.12.008 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Laconi, S., Pirès, S., & Chabrol, H. (2017). Internet gaming disorder, motives, game genres and psychopathology. Computers in Human Behavior , 75, 652-659. 10.1016/j.chb.2017.06.012 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee, C., & Kim, O. (2017). Predictors of online game addiction among Korean adolescents. Addiction Research & Theory , 25(1), 58-66. 10.1080/16066359.2016.1198474 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee, H., Kim, J. W., & Choi, T. Y. (2017). Risk factors for smartphone addiction in Korean adolescents: Smartphone use patterns. Journal of Korean Medical Science , 32(10), 1674-1679. 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.10.1674 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lemmens, J. S., Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2009). Development and validation of a game addiction scale for adolescents. Media Psychology , 12(1), 77-95. 10.1080/15213260802669458 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Li, C., Dang, J., Zhang, X., Zhang, Q., & Guo, J. (2014). Internet addiction among Chinese adolescents: The effect of parental behavior and self-control. Computers in Human Behavior , 41, 1-7. 10.1016/j.chb.2014.09.001 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lim, Y., & Nam, S.-J. (2018). Exploring factors related to problematic internet use in childhood and adolescence. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction , 1-13. 10.1007/s11469-018-9990-9 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lin, M.-P., Ko, H.-C., & Wu, J. Y.-W. (2011). Prevalence and psychosocial risk factors associated with Internet addiction in a nationally representative sample of college students in Taiwan. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking , 14(12), 741-746. 10.1089/cyber.2010.0574 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mehroof, M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2010). Online gaming addiction: The role of sensation seeking, self-control, neuroticism, aggression, state anxiety, and trait anxiety. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking , 13(3), 313-316. 10.1089/cpb.2009.0229 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Milani, L., La Torre, G., Fiore, M., Grumi, S., Gentile, D. A., Ferrante, M., … Di Blasio, P. (2018). Internet gaming addiction in adolescence: Risk factors and maladjustment correlates. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction , 16(4), 888-904. 10.1007/s11469-017-9750-2 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moslehpour, M., & Batjargal, U. (2013). Factors influencing internet addiction among adolescents of Malaysia and Mongolia. Jurnal Administrasi Bisnis , 9(2). [ Google Scholar ]

- Müller, K. W., Janikian, M., Dreier, M., Wölfling, K., Beutel, M. E., Tzavara, C., … Tsitsika, A. (2015). Regular gaming behavior and internet gaming disorder in European adolescents: Results from a cross-national representative survey of prevalence, predictors, and psychopathological correlates. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry , 24(5), 565-574. 10.1007/s00787-014-0611-2 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Peeters, M., Koning, I., & van den Eijnden, R. (2018). Predicting Internet gaming disorder symptoms in young adolescents: A one-year follow-up study. Computers in Human Behavior , 80, 255-261. 10.1016/j.chb.2017.11.008 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Porter, G., Starcevic, V., Berle, D., & Fenech, P. (2010). Recognizing problem video game use. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry , 44(2), 120-128. 10.3109/00048670903279812 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rehbein, F., Psych, G., Kleimann, M., Mediasci, G., & Mößle, T. (2010). Prevalence and risk factors of video game dependency in adolescence: Results of a German nationwide survey. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking , 13(3), 269-277. 10.1089/cpb.2009.0227 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rho, M. J., Jeong, J.-E., Chun, J.-W., Cho, H., Jung, D. J., Choi, I. Y., & Kim, D.-J. (2016). Predictors and patterns of problematic Internet game use using a decision tree model. Journal of Behavioral Addictions , 5(3), 500-509. 10.1556/2006.5.2016.051 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Samarein, Z. A., Far, N. S., Yekleh, M., Tahmasebi, S., Yaryari, F., Ramezani, V., & Sandi, L. (2013). Relationship between personality traits and internet addiction of students at Kharazmi University. International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Research , 2(1), 10-17. [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith, L. J., Gradisar, M., & King, D. L. (2015). Parental influences on adolescent video game play: A study of accessibility, rules, limit setting, monitoring, and cybersafety. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking , 18(5), 273-279. 10.1089/cyber.2014.0611 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Spilkova, J., Chomynova, P., & Csemy, L. (2017). Predictors of excessive use of social media and excessive online gaming in Czech teenagers. Journal of Behavioral Addictions , 6(4), 611-619. 10.1556/2006.6.2017.064 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stavropoulos, V., Kuss, D., Griffiths, M., & Motti-Stefanidi, F. (2016). A longitudinal study of adolescent Internet addiction: The role of conscientiousness and classroom hostility. Journal of Adolescent Research , 31(4), 442-473. 10.1177/0743558415580163 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sul, S. (2015). Determinants of internet game addiction and therapeutic role of family leisure participation. Journal of Inclusion Phenomena and Macrocyclic Chemistry , 82(1-2), 271-278. 10.1007/s10847-015-0508-9 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sun, Y., Zhao, Y., Jia, S.-Q., & Zheng, D.-Y. (2015). Understanding the antecedents of mobile game addiction: The roles of perceived visibility, perceived enjoyment and flow . Paper presented at the Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS). [ Google Scholar ]

- Tian, Y., Yu, C., Lin, S., Lu, J., Liu, Y., & Zhang, W. (2019). Sensation seeking, deviant peer affiliation, and Internet gaming addiction among Chinese adolescents: The moderating effect of parental knowledge. Frontiers in Psychology , 9, 2727. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02727 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Toker, S., & Baturay, M. H. (2016). Antecedents and consequences of game addiction. Computers in Human Behavior , 55, 668-679. 10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.002 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Torres-Rodríguez, A., Griffiths, M. D., Carbonell, X., & Oberst, U. (2018). Internet gaming disorder in adolescence: Psychological characteristics of a clinical sample. Journal of Behavioral Addictions , 7(3), 707-718. 10.1556/2006.7.2018.75 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tsitsika, A., Janikian, M., Schoenmakers, T. M., Tzavela, E. C., Olafsson, K., Wójcik, S., … Richardson, C. (2014). Internet addictive behavior in adolescence: A cross-sectional study in seven European countries. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking , 17(8), 528-535. 10.1089/cyber.2013.0382 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vukosavljevic-Gvozden, T., Filipovic, S., & Opacic, G. (2015). The mediating role of symptoms of psychopathology between irrational beliefs and internet gaming addiction. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy , 33(4), 387-405. 10.1007/s10942-015-0218-7 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Walther, B., Morgenstern, M., & Hanewinkel, R. (2012). Co-occurrence of addictive behaviours: Personality factors related to substance use, gambling and computer gaming. European Addiction Research , 18(4), 167-174. 10.1159/000335662 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wu, J. Y. W., Ko, H.-C., Wong, T.-Y., Wu, L.-A., & Oei, T. P. (2016). Positive outcome expectancy mediates the relationship between peer influence and Internet gaming addiction among adolescents in Taiwan. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking , 19(1), 49-55. 10.1089/cyber.2015.0345 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wu, X.-S., Zhang, Z.-H., Zhao, F., Wang, W.-J., Li, Y.-F., Bi, L., … Hu, C.-Y. (2016). Prevalence of Internet addiction and its association with social support and other related factors among adolescents in China. Journal of Adolescence , 52, 103-111. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.07.012 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Young, K. S. (1998). Internet addiction: The emergence of a new clinical disorder. Cyberpsychology & Behavior , 1(3), 237-244. 10.1089/cpb.1998.1.237 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

- View on publisher site

- PDF (447.4 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 28 November 2022

Psychological treatments for excessive gaming: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Jueun Kim 1 ,

- Sunmin Lee 1 ,

- Dojin Lee 1 ,

- Sungryul Shim 2 ,

- Daniel Balva 3 ,

- Kee-Hong Choi 4 ,

- Jeanyung Chey 5 ,

- Suk-Ho Shin 6 &

- Woo-Young Ahn 5

Scientific Reports volume 12 , Article number: 20485 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

6045 Accesses

4 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

Despite widespread public interest in problematic gaming interventions, questions regarding the empirical status of treatment efficacy persist. We conducted pairwise and network meta-analyses based on 17 psychological intervention studies on excessive gaming ( n = 745 participants). The pairwise meta-analysis showed that psychological interventions reduce excessive gaming more than the inactive control (standardized mean difference [SMD] = 1.70, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.27 to 2.12) and active control (SMD = 0.88, 95% CI 0.21 to 1.56). The network meta-analysis showed that a combined treatment of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Mindfulness was the most effective intervention in reducing excessive gaming, followed by a combined CBT and Family intervention, Mindfulness, and then CBT as a standalone treatment. Due to the limited number of included studies and resulting identified methodological concerns, the current results should be interpreted as preliminary to help support future research focused on excessive gaming interventions. Recommendations for improving the methodological rigor are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Why do adults seek treatment for gaming (disorder)? A qualitative study

A randomized controlled trial on a self-guided Internet-based intervention for gambling problems

The interplay between mental health and dosage for gaming disorder risk: a brief report

Introduction.

Excessive gaming refers to an inability to control one’s gaming habits due to a significant immersion in games. Such an immersion may result in experienced difficulties in one’s daily life 1 , including health problems 2 , poor academic or job performance 3 , 4 , and poor social relationships 5 . Although there is debate regarding whether excessive gaming is a mental disorder, the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) included Gaming Disorder as a disorder in 2019 6 . While there is no formal diagnosis for Gaming Disorder listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), the DSM-5 included Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) as a condition for further study 7 . In the time since the DSM-5’s publication, research on excessive gaming has widely continued. Although gaming disorder’s prevalence appears to be considerably heterogeneous by country, results from a systematic review of 53 studies conducted between 2009 and 2019 indicated a global prevalence of excessive gaming of 3.05% 8 . More specifically, a recent study found that Egypt had the highest IGD prevalence rate of 10.9%, followed by Saudi Arabia (8.8%), Indonesia (6.1%), and India (3.8%) among medical students 9 .

While the demand for treatment of excessive gaming has increased in several countries 10 , standard treatment guidelines for problematic gaming are still lacking. For example, a survey in Australia and New Zealand revealed that psychiatrics— particularly child psychiatrists, reported greater frequency of excessive gaming in their practice, yet 43% of the 289 surveyed psychiatrists reported that they were not well informed of treatment modalities for managing excessive gaming 11 . Similarly, 87% of mental health professionals working in addiction-related institutions in Switzerland reported a significant need for professional training in excessive gaming interventions 12 . However, established services for the treatment of gaming remain scarce and disjointed.

Literature has identified a variety of treatments for excessive gaming, but no meta-analysis has yet been conducted on effectiveness of the indicated interventions. The only meta-analysis to date has focused on CBT 13 , and while results demonstrated excellent efficacy in reducing excessive gaming. However, the study did not compare the intervention with other treatment options. Given that gaming behavior is commonly affected by cognitive and behavioral factors as well as social and familial factors 14 , 15 , 16 , it would also be important to examine the effectiveness of treatment approaches that reflect social and familial influences. While two systematic reviews examined diverse therapeutic approaches, they primarily reported methodological concerns of the current literature and did not assess the weight of evidence 17 , 18 . Given that studies in this area are rapidly evolving and studies employing rigorous methodological approaches have since emerged 19 , 20 , a meta-analytic study that analyzes and synthesizes the current stage of methodological limitations while also providing a comprehensive comparison of intervention options is warranted.

In conducting such a study, undertaking a traditional pairwise meta-analysis is vital to assess overall effectiveness of diverse interventions. Particularly, moderator and subgroup analyses in pairwise meta-analysis provide necessary information as to whether effect sizes vary as a function of study characteristics. Furthermore, to obtain a better understanding of the superiority and inferiority of all clinical trials in excessive gaming psychological interventions, it is useful to employ a network meta-analysis, which allows for a ranking and hierarchy of the included interventions. While a traditional pair-wise analysis synthesizes direct evidence of one intervention compared with one control condition, a network meta-analysis incorporates multiple comparisons in one analysis regardless of whether the original studies used them as control groups. It enters all treatment and control arms of each study, and makes estimates of the differences in interventions by using direct evidence (e.g., direct estimates where two interventions were compared) and indirect evidence (e.g., generated comparisons between interventions from evidence loops in a network 21 . Recent meta-analytic studies on treatments for other health concerns and disorders have used this analysis to optimize all available evidence and build treatment hierarchies 22 , 23 , 24 .

In this study, the authors used a traditional pairwise meta-analysis and network meta-analysis to clarify the overall and relative effectiveness of psychological treatments for excessive gaming. The authors also conducted a moderator analysis to examine potential differences in treatment efficacy between Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) and non-RCTs, age groups, regions, and research qualities. Finally, the authors examined follow-up treatment efficacy and treatment effectiveness on common comorbid symptoms and characteristics (e.g., depression, anxiety, and impulsivity).

The protocol for this review has been registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Review (PROSPERO 2021: CRD 42021231205) and is available for review via the following link: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?RecordID=231205 . Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) network meta-analysis checklist 25 is included in Supplementary Material 1 .

Identification and selection of studies

The authors searched seven databases, which included ProQuest, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, PsycINFO, Research Information Sharing Service (RISS), and DBpia. Given that a substantial number of studies have been published particularly in East Asia and exclusion of literature from the area in languages other than English has been discussed as a major limitation in previous reviews 17 , 18 , the authors gave special attention to gaming treatment studies in English and other languages from that geographical area. Additionally, the authors searched Google Scholar to ensure that no studies were accidentally excluded. The authors conducted extensive searches for studies published in peer-reviewed journals between the first available year (year 2002) and October 31, 2022, using the following search terms: “internet”, or “video”, or “online”, or “computer”, and “game”, or “games”, or “gaming”, and “addiction”, or “addictions”, or “disorder”, “disorders”, or “problem”, or “problems”, or “problematic”, or “disease”, or “diseases”, or “excessive”, or “pathological”, or “addicted”, and “treatment”, or “treatments”, or “intervention”, or “interventions”, or “efficacy”, or “effectiveness”, or “effective”, or “clinical”, or “therapy”, or “therapies”. Search strategies applied to each database is provided in Supplementary Material 2 .

The authors included studies that recruited individuals who were excessively engaging in gaming, according to cutoff scores for different game addiction scales. Since there is not yet an existing consensus on operational definitions for excessive gaming, the authors included studies that recruited individuals who met high-risk cutoff score according to the scales used in each respective study (e.g., Internet Addiction Test [modified in game environments] > 70). The authors also sought studies that provided pretest and posttest scores from the game addiction scales in both the intervention and control groups. Studies meeting the following criteria were excluded: (a) the study targeted excessive Internet use but did not exactly target excessive gaming; (b) the study provided a prevention program rather than an intervention program; (c) the study provided insufficient data to perform an analysis of the effect sizes and follow-up contact to the authors of such studies did not yield the information necessary for inclusion within this paper; and (d) the study conducted undefinable types of intervention with unclear psychological orientations (e.g., art therapy with an undefined psychological intervention, fitness programs, etc.).

Two authors (D.L. and S.L.) independently screened the titles and abstracts of articles identified by the electronic searches and excluded irrelevant studies. A content expert (J.K.) examined the intervention descriptions to determine intervention types that were eligible for this review. All treatments were primarily classified based on the treatment theory, protocol, and descriptions about the procedures presented in each paper. D.L. and S.L.—both of whom have been in clinical training for 2 years categorized treatment type, to which J.K., a licensed psychologist, cross-checked and confirmed the categorization. The authors resolved disagreements through discussion. The specific example of intervention type classification is provided in Supplementary Material 3 .

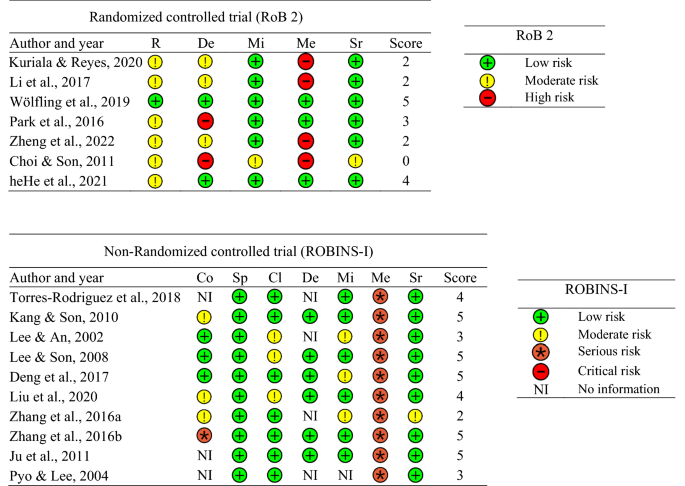

Risk of bias and data extraction

Three independent authors assessed the following risks of bias among the included studies. The authors used the Risk of Bias 2.0 (RoB 2) tool for RCT studies and the Risk Of Bias In Non-Randomized Studies of Intervention (ROBINS-I) tool for non-RCT studies. The RoB 2 evaluates biases of (a) randomization processes; (b) deviations from intended interventions; (c) missing outcome data; (d) measurement of the outcome; and (e) selection of the reported result, and it categorizes the risk of bias in each dimension into three levels (low risk, moderate risk, and high risk). The ROBINS-I evaluates biases of (a) confounding variables; (b) selection of participants; (c) classification of interventions; (d) deviations from intended interventions; (e) missing data; (f) measurement of outcomes; and (g) selection of the reported result, and it categorizes the risk of bias in each dimension into five levels (low risk, moderate risk, serious risk, critical risk, and no information). After two authors (D.L. and S.L.) assessed each study, another author (J.K.) cross-checked the assessment.

For each study, the authors collected descriptive data, which included the sample size as well as participants’ ages, and regions where the studies were conducted. The authors also collected clinical data, including whether the study design was a RCT, types of treatment and control, treatment duration, and the number of treatment sessions. Finally, the authors collected data on the follow-up periods and the measurement tools used in each study.

Data analysis

The authors employed separate pairwise meta-analyses in active control and inactive control studies using R-package “meta” 26 and employed a random-effects model due to expected heterogeneity among studies. A random-effects model assumes that included studies comprise random samples from the larger population and attempt to generalize findings 27 . The authors categorized inactive control groups including no treatment and wait-list control and categorized active control groups including pseudo training (e.g., a classic stimulus-control compatibility training) and other types of psychological interventions (e.g., Behavioral Therapy, CBT, etc.). The authors also used the bias-corrected standardized mean change score (Hedges’ g ) due to small sample sizes with the corresponding 95% confidence interval 28 . The authors’ primary effectiveness outcome was a mean score change on game addiction scales from pre-treatment to post-treatment. Hedges’ g effect sizes were interpreted as small ( g = 0.15), medium ( g = 0.40) and large ( g = 0.75), as suggested by Cohen 29 . The authors used a conservative estimate of r = 0.70 for the correlation between pre-and post-treatment measures 30 , and to test heterogeneity, the authors calculated Higgins’ I 2 , which is the percentage of variability in effect estimates due to heterogeneity among studies rather than chance. I 2 > 75% is considered substantial heterogeneity 31 .

The authors conducted moderator analyses as a function of RCT status (RCT versus non-RCT), age group (adolescents versus adults), region (Eastern versus Western), and research quality (high versus low). The authors divided high versus low quality studies using median values of research quality scores (RCT: low [0–2] versus high [3–5], non-RCT: low [0–4] versus high [5]). The authors calculated Cochran’s Q for heterogeneity: A significant Q value indicates a potentially important moderator variable. For the subgroup analyses of follow-up periods and other outcomes, the authors conducted separate pairwise analyses in 1- to 3-month follow-up studies and in 4- to 6-month follow-up studies and separate analyses in depression, anxiety, and impulsivity outcome studies.

The authors sought to further explore relative effectiveness of treatment types and performed a frequentist network meta-analysis using the R-package “netmeta” 4.0.4 version 26 . To examine whether transitivity and consistency assumptions for network meta-analysis were met, the authors assessed global and local inconsistency. To test network heterogeneity, the authors calculated Cochran’s Q to compare the effect of a single study with the pooled effect of the entire study. The authors drew the geometry plot of the network meta-analysis through the netgraph function in “netmeta”, and the thicker lines between the treatments indicated a greater number of studies.

The authors presented the treatment rankings based on estimates using the surface area under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) 32 . The SUCRA ranged from 0 to 100%, with higher scores indicating greater probability of more optimal treatment. The authors also generated a league table to present relative effectiveness between all possible comparisons between treatments. When weighted mean difference for pairwise comparisons is bigger than 0, it favors the column-defining treatment. Finally, funnel plots and Egger’s test were used to examine publication bias.

Included studies and their characteristics

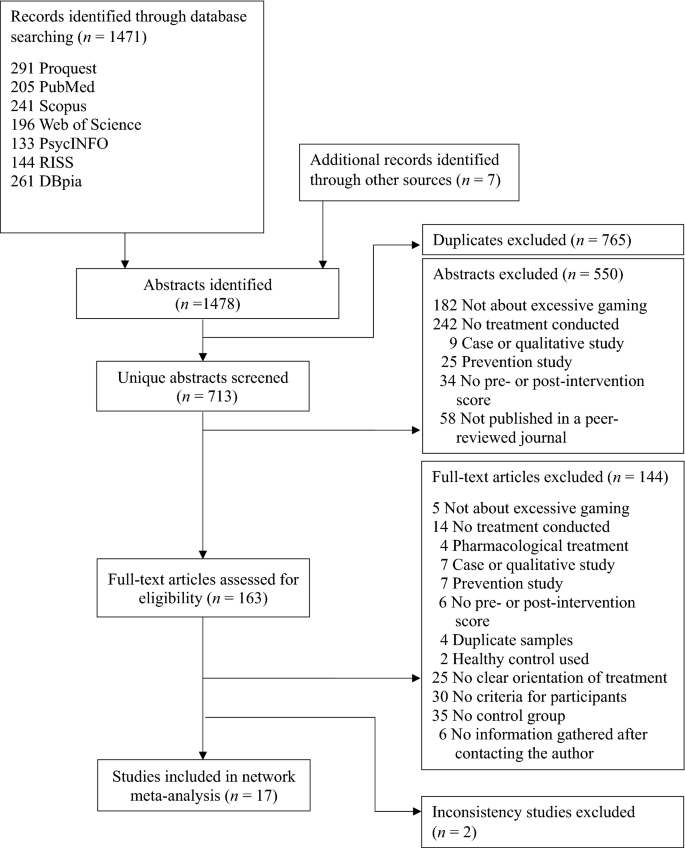

Figure 1 presents the flow diagram of the study selection process. The authors identified 1471 abstracts in electronic searches and identified an additional seven abstracts through secondary/manual searches (total n = 1478). After excluding duplicates ( n = 765) and studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria based on the study abstract ( n = 550), the authors retrieved studies with potential to meet the inclusion criteria for full review ( n = 163). Of these, 144 studies were excluded due to not meeting inclusion criteria based on full-text articles, leaving 19 remaining studies. Of the 19, two studies did meet this paper’s inclusion criteria but were excluded from this network meta-analysis 33 , 34 because the consistency assumption between direct and indirect estimates was not met at the time of this study's consideration based on previous studies 35 , 36 . Therefore, a total of 17 studies were included in this network meta-analysis, covering a total of 745 participants 36 .

Flow diagram of the study selection process.

Table 1 lists the characteristics of the 17 included studies. CBT ( n = 4), Behavioral Treatment (BT) + Mindfulness ( n = 4), and BT only ( n = 4) were most frequently studied, followed by CBT + Family Intervention ( n = 1), CBT + Mindfulness ( n = 1), virtual reality BT ( n = 1), Mindfulness ( n = 1), and Motivational Interviewing (MI) + BT ( n = 1). Seven studies were conducted in Korea and six were conducted in China, followed by Germany and Austria ( n = 1), Spain ( n = 1), the United States ( n = 1), and the Philippines ( n = 1). Twelve articles were written in English, and five articles were written in a language other than English. Nine studies conducted a follow-up assessment with periods ranging from one to three months, and two studies conducted a follow-up assessment with periods ranging four to six months. In one study 20 , the authors described their 6-month follow-up but did not present their outcome value, and thus only two studies were included in the four- to six-month follow-up analysis. Among the 17 included studies, eight had no treatment control group, five had an active control group (e.g., pseudo training, BT, and CBT), and four had a wait-list control group. Seven of the studies were RCT studies, and 10 were non-RCT studies.

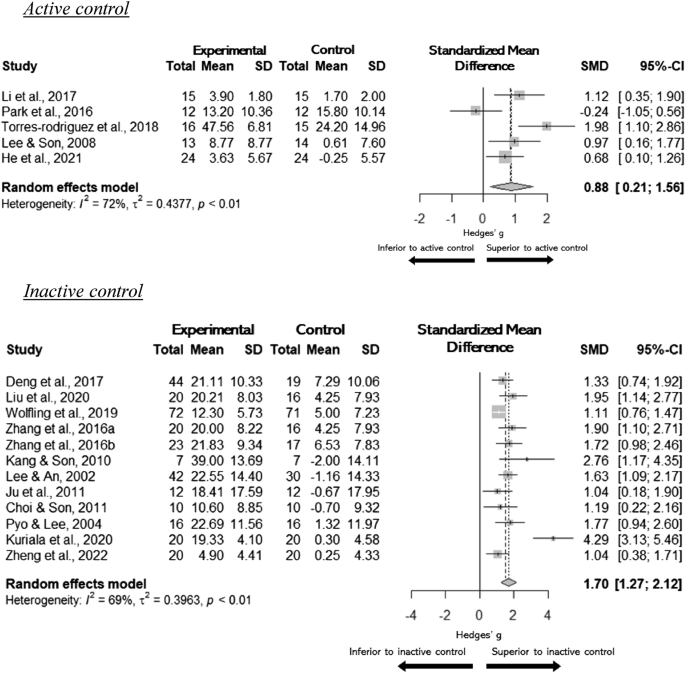

Pairwise meta-analysis

The results of meta-analyses showed a large effect of all psychological treatments when compared to any type of comparison groups ( n = 17, g = 1.47, 95% CI [1.07, 1.86]). The treatment effects were separately provided according to active versus inactive comparison groups in Fig. 2 . The effects of psychological treatments were large when compared to the active control ( n = 5, g = 0.88, 95% CI [0.21, 1.56]) or inactive control ( n = 12, g = 1.70, 95% CI: [1.27, 2.12]). Substantial heterogeneity was evident in studies that were compared to both the active controls (I 2 = 72%, < 0.01) and inactive controls at p -value level of 0.05 (I 2 = 69%, p < 0.001).

Pairwise Meta-analysis. Psychological treatment effects on excessive gaming by comparison group type (active and inactive controls). SMD standardized mean difference, SD standard deviation, CI confidence interval, I 2 = Higgins' I 2 .

Moderator analysis

As shown in Table 2 , the moderator analysis suggested that effect sizes were larger in non-RCT studies ( n = 10, g = 1.60, 95% CI [1.36, 1.84]) than RCT studies ( n = 7, g = 1.26, 95% CI [0.30, 2.23]). However, the results of a Q-test for heterogeneity yielded insignificant results (Q = 0.44, df[Q] = 1, p = 0.51), indicating that no statistically significant difference in treatment efficacy at p level of 0.05 between RCT and non-RCT studies.

The results of Q-test for heterogeneity did not yield any significant results, indicating no significant differences in treatment efficacy between adults and adolescents (Q = 2.39, df[Q] = 1, p = 0.12), Western and Eastern regions (Q = 0.40, df[Q] = 1, p = 0.53), or low and high research qualities among RCT studies (Q = 2.25, df[Q] = 1, p = 0.13) and non-RCT studies (Q = 3.06, df[Q] = 1, p = 0.08).

Subgroup analysis

The results demonstrated that the treatment effect was Hedges’ g = 1.54 (95% CI [0.87, 2.21]) at 1-to-3-month follow-up and Hedges’ g = 1.23 (95% CI [0.77, 1.68]) 4- to-6-month follow-up. The results also showed that the treatment for excessive gaming was also effective on depression and anxiety. Specifically, treatment on depression was Hedges’ g = 0.52 (95% CI: [0.22, 0.81], p < 0.001), and anxiety was Hedges’ g = 0.60 (95% CI [0.11, 1.08], p = 0.02), which are medium and significant effects. However, the effect on impulsivity was insignificant, Hedges’ g = 0.26 (95% CI [− 0.14, 0.67], p = 0.20).

Network meta-analysis

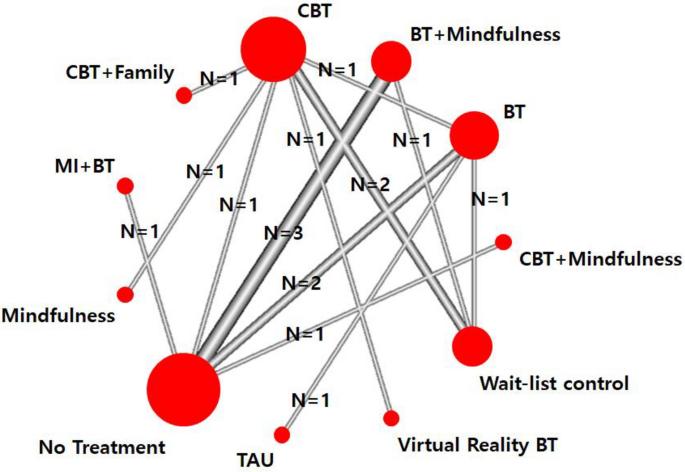

As shown in Fig. 3 , a network plot represents a connected network of eight intervention types (CBT, BT + Mindfulness, BT, Virtual Reality BT, CBT + Mindfulness, CBT + Family, MI + BT, and Mindfulness) and three control group types (wait-list control, no treatment, treatment as usual). The widest width of nodes was observed when comparing BT + Mindfulness and no treatment, indicating that those two modules were most frequently compared. No evidence of global inconsistency based on a random effects design-by-treatment interaction model was found (Q = 8.5, df[Q] = 7, p = 0.29). Further, local tests of loop-specific inconsistency did not demonstrate inconsistency, indicating that the results from the direct and indirect estimates were largely in agreement ( p = 0.12- 0.78).

Network plot for excessive gaming interventions. Width of lines and size of circles are proportional to the number of studies in each comparison. BT behavioral therapy, CBT cognitive behavioral therapy, Family family intervention, MI motivational interviewing, TAU treatment as usual.

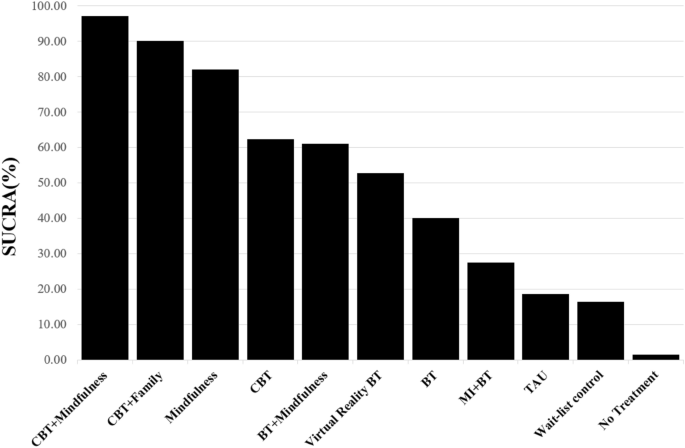

As shown in Fig. 4 , according to SUCRA, a combined intervention of CBT and Mindfulness ranked as the most optimal treatment (SUCRA = 97.1%) and demonstrated the largest probability of effectiveness when compared to and averaged over all competing treatments. A combined treatment of CBT and Family intervention ranked second (SUCRA = 90.2%), and Mindfulness intervention ranked third (SUCRA = 82.1%). As shown in Table 3 , according to league table, CBT + Mindfulness intervention showed positive weighted mean difference values in the lower diagonal, indicating greater effectiveness over all other interventions. The CBT + Mindfulness intervention was more effective than CBT + Family or Mindfulness interventions, but their differences were not significant (weighted mean differences = 0.23–1.11, 95% CI [− 1.39 to 2.68]). The top three ranked interventions (e.g., CBT + Mindfulness, CBT + Family intervention, and Mindfulness in a row) were statistically significantly superior to CBT as a standalone treatment as well as the rest of treatments.

Surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) rankogram of excessive gaming. BT behavioral therapy, CBT cognitive behavioral therapy, Family family intervention, MI motivational interviewing, TAU treatment as usual.

Risk of bias

Figure 5 displays an overview of the risk of bias across all included studies. Of note was that in the RCT studies, bias due to missing outcome data was least problematic, indicating a low dropout rate (six out of seven studies). In contrast, bias due to deviations from intended interventions was most problematic, indicating that, in some studies, participants and trial personnel were not blinded and/or there was no information provided as to whether treatments adhered to intervention protocols (six out of seven studies). In the non-RCT studies, bias in the selection of participants in the study was least problematic, indicating that researchers did not select participants based on participant characteristics after the start of intervention (10 out of 10 studies). In contrast, bias in the measurement of outcomes was most problematic, indicating that participants and outcome assessors were not blinded and/or studies used self-reported measures without clinical interviews (10 out of 10 studies).

Overview of risk of bias results across all included studies. Cl bias in classification of interventions, Co bias due to confounding, De bias due to deviations from intended interventions, Me bias in measurement of the outcome, Mi bias due to missing outcome data, R bias arising from the randomization process, RoB risk of bias, ROBINS-I risk of bias in non-randomized studies of intervention, Sp bias in selection of participants in the study, Sr bias in selection of the reported result.

Funnel plots and Egger’s test showed no evidence of publication in network meta-analyses. Funnel plots were reasonably symmetric and the result from Egger’s test for sample bias were not significant ( p = 0.22; see Supplementary Material 4 ).

In this pairwise and network meta-analyses, the authors assessed data from 17 trials and analyzed the overall and relative effectiveness of eight types of psychological treatments for reducing excessive gaming. The pairwise meta-analysis results indicated large overall effectiveness of psychological treatments in reducing excessive gaming. Although the effectiveness was smaller when compared to the active controls than when compared to the inactive controls, both effect sizes were still large. However, this result needs to be interpreted with caution because there are only seven existing RCT studies and several existing low-quality studies. Network meta-analysis results indicated that a combined treatment of CBT and Mindfulness was the most effective, followed by a combined therapy of CBT and Family intervention, Mindfulness, and then CBT as a standalone treatment, however, this finding was based on a limited number of studies. Overall, the findings suggest that psychological treatments for excessive gaming is promising, but replications are warranted, with additional attention being placed on addressing methodological concerns.

The large effect of psychological treatments in reducing excessive gaming seems encouraging but the stability and robustness of the results need to be confirmed. These authors’ moderator analysis indicated that the effect size of non-RCT studies was not significantly different from that of RCT studies. The authors conducted a moderator analysis using the research quality score (high vs low) and found that research quality did not moderate the treatment effect. The authors also examined publication bias using both funnel plots and Egger’s test and found no evidence of publication bias in network meta-analysis. Because most of the studies included in the review were from Asian countries, the authors examined the generalizability of the finding by testing moderator analysis by regions and found no significant difference of treatment effect sizes between Eastern and Western countries. Finally, although limited studies exist, treatment benefits did not greatly diminish after 1–6 months of follow-ups, indicating possible lasting effects.

Network meta-analysis findings provide some preliminary support for the notion that a combined treatment of CBT and Mindfulness and a combined treatment of CBT and Family intervention are most effective in addressing individuals’ gaming behaviors. These combined therapies were significantly more effective than the CBT standalone approach. CBT has been studied and found to be highly effective in addiction treatment—particularly in reducing excessive gaming due to its attention to stimulus control and cognitive restructuring 13 . However, adding Mindfulness and family intervention may have been more effective than CBT alone, given that gaming is affected not only by individual characteristics, but also external stress or family factors.

Mindfulness generally focuses on helping individuals to cope with negative affective states through mindful reappraisal and aims to reduce stress through mindful relaxation training. The effectiveness of Mindfulness has been validated in other substance and behavioral addiction studies such as alcohol 37 , gambling 38 , and Internet 39 addiction treatments. Indulging in excessive gaming is often associated with the motivation to escape from a stressful reality 40 , and mindful exercises are likely to help gamers not depend on gaming as a coping strategy.

Because excessive gaming is often entangled with family environments or parenting-related concerns—particularly with adolescents, addressing appropriate parent–adolescent communication and parenting styles within excessive gaming interventions are likely to increase treatment efficacy 41 , 42 , 43 . Based on a qualitative study focused on interviews with excessive gamers 43 , and per reports from interviewed gamers, parental guidance to support regulatory control and encouragement to participate in other activities are important factors to reduce excessive gaming. However, at the same time, if parents excessively restrict their children’s behavior, children will feel increased stress and may further escape into the online world through gaming 44 as a means of coping with their stress. Our study indicates that appropriate communication among parents and adolescents in addition to parenting styles with respect to game control must be discussed in treatment. However, because only two studies examined the top two ranked combined interventions within this paper, such findings warrant replication.

Limitations and future directions

These authors identified methodological limitations and future directions in the reviewed studies, which include the following. The authors included non-RCTs to capture data on emerging treatments, but a lack of RCT studies contributes to this paper’s identified methodological concerns. Of 17 studies included, seven were RCT studies and 10 were non-RCT studies. The lack of RCT studies has been repeatedly mentioned in previous review studies 17 , 18 . In fact, one of the two identified reviews 17 made the criticism that even CBT (the most widely studied treatment for excessive gaming) was mostly conducted in non-RCT studies, which was commensurate with this paper’s data (only one out of four CBT studies included in this review is a RCT). Including non-RCTs may be likely to increase selection bias by employing easily accessible samples and assigning participants with more willingness (which is an indicator of better treatment outcome) to intervention groups. Selection bias may have increased the effect size of treatments than what is represented in reality and may limit the generalizability of this finding. Thus, more rigorous evaluation through RCTs is necessary in future studies.

While there are concerns surrounding assessment tools, given that all included studies used self-report measures without clinical interviews, this may lead to inaccurate results due to perceived stigma. Additionally, 11 self-reported measurement tools were employed in the included studies—and some of those tools may have poor sensitivity or specificity. A previous narrative review 45 and a recent meta-analytic review 46 suggested that the Game Addiction Scale-7, Assessment of Internet and Computer Addiction Scale-Gaming, Lemmens Internet Gaming Disorder Scale-9, Internet Gaming Disorder Scale 9- Short Form, and Internet Gaming Disorder Test-10 have good internal consistency and test–retest reliability. Thus, there is a need for studies to employ clinical interviews and self-report measures with good psychometric features.

Many studies in this included review did not describe whether participants and experimenters were blinded and there was no information about whether treatments adhered to intervention protocols. Although blinding of participants and personnel may be impossible in most psychotherapy studies, it is crucial to evaluate possible performance biases such as social desirability. Also, a fidelity check by content experts is needed to confirm whether treatments adhered to intervention protocols.