Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Why People Make Sacrifices for Others

In 2007, 50-year-old Wesley Autrey of New York City was standing on a subway platform when he saw a man nearby suffer a seizure and fall onto the tracks. As the light of an oncoming train appeared, “I had to make a split decision,” reported Autrey.

Leaving his two young daughters on the platform, he leapt in front of the train and pinned the man to the ground as the train rumbled overhead, saving the man’s life. When asked later why he risked his life for a stranger, Autrey replied, “I did what I felt was right.”

What explains the feeling that drove Mr. Autrey to endanger himself in order to help someone else?

A recent study led by Oriel FeldmanHall, a post-doctoral researcher at New York University, tested two dominant theories about what motivates “costly altruism,” which is when we help others at great risk or cost to ourselves.

FeldmanHall and her colleagues examined whether costly altruism is driven by a self-interested urge to reduce our own distress when we see someone else suffering or whether it’s motivated by the compassionate desire to relieve that other person’s pain.

In the study, the researchers first had people take a survey measuring how strongly they react to others’ suffering with feelings of compassionate concern or with feelings of personal distress and discomfort.

Then, they gave everyone some money—20 pounds (the study was conducted in the UK)—with the chance to keep or lose one pound in each of 20 rounds.

How much money they got to keep each round depended on how willing they were to administer painful shocks to a person in another room with whom they had interacted briefly. If they chose to administer the highest intensity shock, they got to keep the whole pound; if they administered a less intense shock, they kept less of the money; and if they decided to forgo administering a shock at all, they relinquished the entire pound.

After making their decision, the study participants watched a video showing the consequences of their decision. Unbeknownst to the participants, the video was actually a pre-recorded scene of the person pretending to be shocked or not shocked—no one was actually harmed. Through each step of the process, the participants’ brains were being scanned in an fMRI machine, which tracked their brain activity.

FeldmanHall’s team found that participants who generally respond to suffering with compassionate concern (rather than distress or discomfort) gave up more money. While watching the results of their decisions, all participants showed increased activity in brain circuits associated with empathy.

However, compared with the other participants, when the more compassionate people watched videos showing the outcome of their own generosity—people being shocked at low levels, or not at all—their brains showed greater activity in regions associated with feelings of pleasure and socially rewarding states, like maternal love.

More selfish choices, on the other hand, were associated with activation of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), a brain region often implicated in distress related to internal conflict and the inhibition of intuitive behaviors, and of the amygdala, the brain’s putative vigilance-to-threat detector.

From these results, the researchers surmise that acts of costly altruism are more strongly associated with feelings of compassionate concern than with a selfish need to relieve one’s own distress. This is consistent with prior research suggesting that when people experience distress in response to someone else’s suffering, they’re more likely simply to avoid that person than try to help.

Fortunately, prior research also suggests that compassion isn’t simply a fixed trait; instead, it seems possible to increase your capacity for it over time—for instance, by broadening your social networks, actively trying to take someone else’s perspective, or even by meditating. Through these steps, you might not only strengthen your ability to connect with others, but as FeldmanHall’s study suggests, you might also strengthen your capacity for selflessness.

About the Author

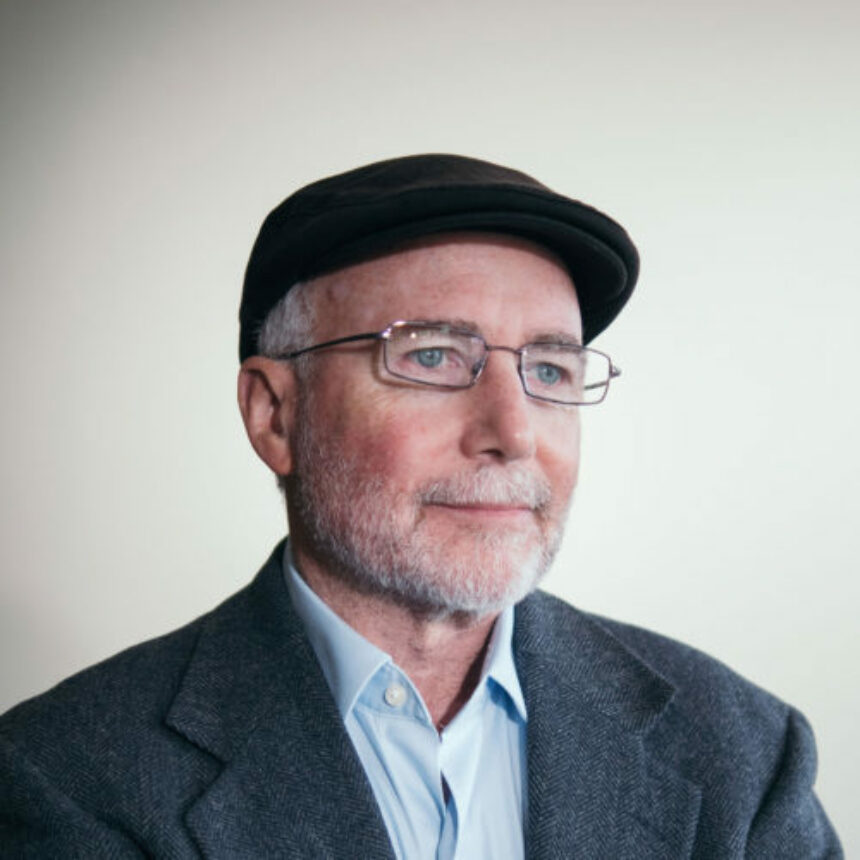

Josh Elmore

Joshua Elmore is an undergraduate psychology student at UC Berkeley and a scholar with the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation. He is also a research assistant for the Greater Good Science Center and the Relationships and Social Cognition Lab at UC Berkeley.

You May Also Enjoy

The Morality of Global Giving

Altruism in Space

Is There an Altruism Gene?

The Altruistic Advantage

Five Lessons in Human Goodness from “The Hunger Games”

The Altruistic Electorate

Feb 19, 2021

The Freedom of Self-Sacrifice

Mark Damien Delp

Zaytuna College

Mark Damien Delp’s research interests include logic and the history of Christian philosophy.

Rediscovering the Ancient Roots of Moral Action in the Late-Modern Twilight of Free Will

And We Are Trying, N. Roerich, n.d.

Among the revolutionary changes brought about by modern technology and its growing role in shaping human behavior, the most alarming have to do with our ability—and right—to come to our own decisions about things that bear on our dignity as human persons. We continue to have vital human impulses, natural loves and fears, aspirations that resemble those of premodern societies, and sensibilities that find their home in a great variety of religious institutions. All the same, it seems that in our acquired habitual interface with social media platforms, we are actively ceding the essential part of our humanity, rational volition, to an intimate but mostly unnoticed symbiosis with a nonhuman mind, whose coercive thought and will mix so thoroughly with our own that we can hardly tell where one ends and the other begins.

Ultimately, however, the hope is that we won’t just use computers—we’ll become them. Today, cognitive scientists often compare the brain to hardware and the mind to the software that runs on it. But a software program is just information, and in principle there’s no reason why the information of consciousness has to be encoded in neurons. 1

The most evident sign of this compromise to our free will is found in the fact that we now make most of our decisions not by deliberation and consultation, which draw from the deeper regions of human passion and require the ordering influence of our native reason, but by subtle inclinations of desire and fear that, detached from that reason, are shaped and channeled by the artificial intelligence of corporate algorithms.

“When all that says ‘it is good’ has been debunked, what says ‘I want’ remains.” 2

It is common knowledge in the social media industry that people do not really choose to follow trends but are moved to do so by subliminal coercion. Immersed in the confidence that one is making personal decisions, one actually merely submits to the ephemeral pleasure of participating in mass, collective decisions, the consequences of which neither interest the individual nor touch his conscience, the moral witness of all acts of free will. By an artificially induced necessity, we now think algorithmically; although algorithms themselves are human constructs, like other mathematical systems they measure only a small, quantitative part of us that is detached from our qualitative aspects, the unity of which we mysteriously grasp in our idea of the human person. Nonetheless, many have begun to suspect that we have reached a threshold at which a real choice must be made—namely, whether to preserve the primordial spark of our humanity or, appalled and repulsed by late-modern presentations of human history on the one hand and entranced by stories of a “transhuman” 3 life on the other, to leave it behind once and for all. Presuming that the former is the only choice a human being can make—choosing, after all, being a human thing to do 4 —the immediate task is to find out what is happening to us in the human interface with social media algorithms. 5 Fortunately, there is growing evidence, produced by many who are intimately involved in creating, managing, and using social media, that reveals how corporate algorithms have been compromising our free will and, consequently, changing the innate orientation of our moral compass.

W e are “losing our free will .” Through algorithms that monitor our behavior and activities, Google and other free social media are changing our behavior without our even knowing it. 6

The vast majority of us communicate with these algorithms far more often than we speak with human persons; accustomed to thinking of online platforms as merely passively registering consumer demands and facilitating routine searches for information, most people are ignorant of or unconcerned with the platforms’ more important task, which is at once to study and to manipulate human behavior, shaping and channeling our decision-making processes from relatively superficial to profoundly subliminal levels of consciousness.

What might once have been called advertising must now be understood as continuous behavior modification on a titanic scale, but without informed consent. 7

You work on algorithms... until you find a formula that will cause behavior change, or behavior pattern change, in a predictable manner.... This is something entirely new in the world and distinct from any previous advertising, or policing, or statecraft. 8

The actual user interface can harm individuals, especially children, 9 but the injuries, psychological as well as physiological, can be concealed or explained away by citing the overall benefit of that interface to consumers. To some observers, however, the extent to which social media corporations will go to pursue coercive agendas reveals a capacity and commitment to effect deeper and more permanent modifications in human behavior than was heretofore possible in the advertising industry. Software engineers have become, for all intents and purposes, social engineers.

We’re being tracked and measured constantly, and receiving engineered feedback all the time. We’re being hypnotized little by little by technicians we can’t see, for purposes we don’t know. We’re all lab animals now. 10

Given the societal saturation of handheld devices, it is not surprising that people in every sector of society are now thoroughly used to conducting their business by using online platforms and speaking to computer simulations of human voices; but that they have so easily shifted into using a machine interface in order to communicate, in the most intimate fashion, with loved ones and friends continues to be astounding, especially given the invisible audience of anonymous data harvesters that not only monitor our every word but statistically harvest our emotions.

The Ancient World: Free Will amid Suffering and Love

Of all the things we possess, our rational free will is the most precious, but it is usually only in the shock of its imminent loss—or, in the present context, theft—that we cling to it with the appropriate ferocity. The question of whether free will is real or an illusion 11 ceases to matter when it is existentially threatened—when, that is, a panic takes hold of our body and mind, making us cry out for a sense of purpose we may have never known. While there is no shortage of witnesses to the terrible risks posed to humanity by online platforms, especially social media, the strength of current statistical analyses and compilations of the available data on the crisis is offset by a lack of qualitative reflection concerning the spiritual structures of human moral agency, which have traditionally been treated by religion. Specifically, Western civilization presupposes a vast literature on “the free choice of the will,” 12 the culmination of which we find in Thomas Aquinas’s writings in moral theology. The common characteristic of this tradition is its aim not only to guide human actions toward virtuous ends but to discover the inner workings of the human reason and will that are required to achieve them. There exists, in short, an alternate fund of research, equally scientific in its own fashion, that meticulously documents the subtle order involved in the many stages of rational volition as well as its influence on the passions—i.e., desire, anger, fear, and so on. Seeking to give them measure and grace, the authors in this tradition recognized that controlling the passions was neither desirable nor possible. The research of contemplative intuition revealed that, together with these impulses, the internal expansiveness of imagination and intellect sets to work in the various dimensions of the will, from which then flow practical acts that mold external circumstances into well-ordered and harmonious wholes. The path of moral virtue, though beginning in robust confrontation with external circumstances, always saw its end in internal perfection.

Man and Machine, Hannah Hoch, 1921

Aquinas called moral acts “human acts,” for he held that moral virtues make sense only in the context of the entire human person that is perfected by them. But the fundamental structure, itself premoral, that allows the human being to act at all is the network of means and ends, which also happens to be the language of teleology. In his Summa Theologica , 13 he maintains that “all things, by desiring their own perfection, desire God himself.” To modern sensibilities, this will seem to be merely one of many anthropomorphic statements to which ancient philosophers were given in their attempts to account for an order in nature that requires a mathematical language they did not possess. Despite what we are usually told, both modern and ancient sciences have held, as a fundamental principle, that nature is built on rational structures. The greatest difference between the two perspectives has, rather, to do with whether there is teleology in nature—that is, whether all things act for the sake of something . For Aristotle, to whom Aquinas was obliged for the background of his statement, every being moves toward the perfection of its own nature by something approximating human desire, be it natural impulse, instinct, or the complex affective life of the higher animals. To take some obvious examples, birds build nests for the sake of propagating, and a single bird will fly in the face of a predator for the sake of protecting its mate. The bird’s passion, as it were, drives the rational goal of preserving its young even while the rational goal gives structure to the passion. Thus, while moderns have been content to limit rationality in nature to mathematical patterns and causal predictability, the ancients required in things a final causality that accounts not only for rational structures but also the vital forces that sustain them. But while nature as a whole acts rationally, they held that only the human species actually possesses a rational faculty . This legacy of teleology in the philosophy of nature laid the groundwork for later scholastic philosophers to treat the rationality of human actions as a special application, as it were, of the more universal order of natural causes. While the natural philosopher conceived of the final cause of things as that for the sake of which they move by natural impulse, the ethicist posited the final cause in human acts as the end for the sake of which one chooses the means. And while other animals simply desire the end, the human animal desires it self-consciously as “good.”

The second source for Aquinas’s statement can be found in the theology of the early church, which, though it agreed with Aristotle that all things desire in analogous ways their own perfection, was compelled to expand his teleology to conform to the belief that all things are created by God—that is, they are creatures. The church fathers assigned, therefore, a twofold end to all things: the first being their natural end, which is simply the mature form of their species (a baby robin works hard to be a fully grown robin); the second being their providential end, the end that makes their specific motions contribute to a universal or cosmic plan designed by their creator. 14 It was this second end that ultimately accounted for the fact that a rational structure, such as a robin’s nest, can be constructed by a creature without a rational faculty. Traditional Christian theology, therefore, added to Aristotle’s scientific anthropomorphism a comprehensive “theomorphism.”

All things move for the sake of ends; but we alone can will the end in such a way that we reflectively evaluate the means that can achieve it and choose them by deliberation. Moreover, the complexity of human acts, their layered self-consciousness, and the variety of their volitional modes require a far greater amount of time and space to reach their completion than those of other creatures. The difference is staggering if one considers the great variety that can be found in human plans, some of which take many years to unfold and include a vast network of means and ends by which the final end might be accomplished. The rich rationality of human acts demands a fullness of time and space, but it is the end, which comes from outside us, that constitutes the intelligible light by which our acts derive meaning and purpose. Accordingly, we love the end not merely as a goal or terminus but as something good in itself. Though we may not love the means, it has traditionally been a mark of maturity in a person to respect them, to develop a relation with them that is marked by patient attention and care as to their own requirements.

The self-consciously rational and reflective nature of the human network of means and ends begets another property unique to humans—namely, that some means become so desirable in themselves that they become ends in their own right, even as they continue to be the means toward a more remote and greater good. This property of human means is an important witness to the spatiotemporal dimensions required by human acts. Consider the arts of grammar, logic, and rhetoric, which, though regarded as the means for achieving wisdom, reflect the beauty of that end to such an extent that they have become, over millennia of use, ends and goods in themselves. With respect to most means, however, the best we can hope for is toleration, as is often the case with those we accomplish each day merely “to get on with our lives.” Consequently, a crucial part of deliberating as to which means we should choose to achieve the end is finding the ones that are the least burdensome—that is, that involve the least suffering. We are sometimes constrained to choose between means that are very unpleasant indeed, and which only a very beloved or necessary end can justify by bringing them under its overarching goodness. As a rule, then, we suffer the means and enjoy the end.

There is also, however, a suffering that is proper to love, for as long as the beloved object is out of reach we must endure its absence, and the course of that endurance can be painful indeed. Further, if love did not suffer the privation of its object, there would be no such thing as the means, for we would always possess whatever we love. Love thus generates the means and, in doing so, generates their characteristic suffering. Though the suffering of privation is found in every living being, in human acts it can reach such an intensity as to become indistinguishable from the love that begets it, as we will see further on. And since, in the more complex human acts, means themselves become subordinate ends, we also suffer privation with respect to them. St. Augustine of Hippo, speaking from personal experience, noted that the excessive love of the means can result in a fatal delay in the soul’s journey to God, thus putting the love of the means into competition with the love even of our absolute and final end: happiness. We must also point out that because the network of means can range from the optional to the necessary, human acts come naturally arranged in a hierarchy of suffering and love, the latter constituting the characteristic passion regarding ends, the former the characteristic passion regarding the means. Finally, if every voluntary act involves this twofold suffering in its means and ends, and if every society is held together by voluntary acts, then every society will be made up of a network of love and suffering.

Self-Sacrifice and the Common Good

As the theoretical sciences isolate certain extreme examples of their subjects as archetypes for all the rest, so the practical science of moral theology, in the process of studying virtuous actions, seeks particular examples in which they attain extremes of passionate intensity. Such qualitative intensity in a virtue becomes all the more important to moral theology in comparison with classical ethics insofar as moral theology considers its subjects in light of their supernatural as well as their natural perfection—that is, both with respect to their remote and their proximate ends. Accordingly, loves and sufferings that society condones as common features of its normative life and, thus, considers to be ethical can be raised to such a qualitative intensity that, precisely because they disrupt the accustomed order of human passions, they require a theological consideration to account for their meaning and purpose. More to our point, when confronted by circumstances of extreme adversity, ordinary relations of love can be condensed to such a degree that the time required to reflect on them shrinks to a single instant of fierce necessity. When the mother’s naturally affectionate love for her child is immediately and mortally threatened, it can become so intense as to make her aware of nothing but things that may be enlisted in her spontaneous efforts to preserve the child’s life—things that may include her own life. For the moral theologian interested in the boundary between the natural and the supernatural virtues, 15 among the lessons to be learned from such a crisis of love is that it is a likeness to the highest kind of religious love for God, what the tradition has called “mystical love”: as the mother, in a moment of fierce loving care, has no sense of herself apart from her child, so the mystic, with an analogously fierce love for God, has no sense of herself apart from God. Here we do not speak of doing something for another but rather of being for the sake of another, the latter of which allows no time or space for self-consciousness, let alone for deliberation, counsel, or choice, the natural phases of every human act according to moral theology. Even means and ends become indistinguishable from each other when, in a single instant, love and suffering become a single passion.

Monhegan, Maine, N. Roerich, n.d.

In ancient Greek usage, the verb pasco (to suffer) commonly signified the passive experience of unpleasant as well as pleasant things; gradually, however, the verb came to signify exclusively with respect to unpleasant or inimical things. 16 At some point, one ceased to “suffer joy” at any happy circumstance, although expressions of “suffering love” managed to escape the inadvertent linguistic purge. In early Christian literature, however, pasco and its various derivatives began to be conceived in such an altered way as almost to constitute a shift in their essential meaning: in addition to signifying “bearing the burden of something distressing or painful,” it came also, and even principally, to signify “suffering for the sake of God.” 17 In subsequent Christian literature the meanings attached to suffering became even more complex, including, over and above self-denial in the pursuit of God, self-sacrifice in bearing witness to Christ. 18 In the martyr, the archetype of Christian self-sacrifice, the act of suffering became self-conscious in a way that was lacking even in heroic acts of suffering death for the sake of family or country, acts that were not done explicitly for the sake of witnessing to God. The martyr, having separated himself from concern with any object or end apart from God, deliberately, and at the height of his passion, made his very self the sole means of witnessing to Him. Indeed his self, which had always distracted him from God, had become the last privation of his love for God, the last obstacle to becoming one with Him, and, thus, it had become his suffering. And because love and suffering are correlative, the martyr’s love shared in the intensity of his suffering, much as the mother’s suffering shared in her love. Finally, as every worldly love manifests the suffering that arises from the privation of a good, so too, in the martyr’s love of the highest Good, could be found the highest expression of human privation.

But at this point one may ask, What is the purpose of these extremes of love and suffering for maintaining the bonds of society and the common good? How can they be the means for the immediate end of preserving the health and welfare of citizens? For the passions of martyrs and heroes ultimately bear witness to the dissolution, not the preservation, of the normative bonds of human relations. The mother suffers for her child, the martyr for God, but neither dies for society. 19 The mother loves nothing but her child, the martyr nothing but God, but neither of these intensive loves is capable of being shared extensively among others. These so-to-speak non-societal loves, however, are akin to the type of love designated in Greek as eros , a term that, while signifying in classical literature the intensity of romantic love, was adopted by the early church to signify the human person’s absolute love of God. And as the love of God, being free from corporeal passions, is shrouded in mystery to those who still love the things of this world, it was often qualified by the term mystical . Mystical eros was thought to be the glue that binds a solitary soul to God, and because it was every bit as exclusive as that of the mother and the martyr, it could not, per se, be the glue that binds individuals with each other in a community, even in a community of the faithful or the ecclesia . 20 In Egypt and Palestine, Christians living in the cities went out to the desert to take counsel with anchorites , 21 hermits who had renounced human society for the sake of continuous prayer. Nonetheless, the fathers of the early church believed that the love which is proper to community—namely, agape or “filial love”—was not different in kind to mystical love, and though they held that the former is weaker than the latter, by weaker they did not mean feeble or ignoble but extensive rather than intensive ; agape was designed, as it were, to be the absolute love of God expressed relatively as the love of neighbor. Their common element, that which made them extremes of the same kinship of divine love, was self-sacrificial suffering—in eros, the absolute self-sacrifice for the sake of God; in agape, the relative self-sacrifice for the sake of another. Agape, then, is mystical eros as suffered in the world.

In the ecclesia, every secular relation took on an added dimension, an otherworldliness that directed the eye beyond the beloved person to the source of love itself, and did so without diminishing the love of human kinship. With agape, the benevolent relations of human society and the affection generated therein became at once heightened in their intensity and strengthened in their adhesive power to bind persons to each other, for all relations were essentially self-sacrificial. The filial love of agape is essentially relative in the sense that one calls the members of one’s extended family “relatives,” but because it is otherworldly as well, it inspires a hope that turns the mind to the love that is not mediated by any worldly relation. Far from constituting a utopia (which makes itself the end), or a dystopia (which is the actual end of a utopia), the ecclesia might be called a prostopia , a community that, qua community, is directed toward and in essential relation to another place—the place of God. The expression in Greek for relation is pros ti , literally, “toward something,” but in an ecclesia, the relation between citizens is raised to the level of being pros theon , a being-toward-God. Here we see the twofold end of all things, mentioned above, as functioning in the microcosm of human society, in which each citizen is acutely conscious of his natural and supernatural end, of his love for neighbor and his love for God. Each person reminds the other of the Person of God, and in this way guarantees that the community will be filled with a supernatural joy of human kinship that, being proper to agape, does not enter into mystical eros, for which God is present to the point of making all others absent. Nonetheless, just as there can be no means without an end, so the complete love of agape would not be possible without the mystical love that transcends it.

The most important father of the early Latin church, St. Augustine, asserted that the true love of God was the only love we should enjoy as a good in itself, and that every love we have for others, be they spouses, family, or friends, can never be more than the means toward that end. He went so far as to say that we should use others for the sake of cultivating our absolute relation to God. At first glance this seems a heartless proposition, one designed not to foster love between people but to alienate them from each other, to dissolve rather than constitute the glue holding them together. But he made it quite clear that far from diminishing the legitimacy and qualitative intensity of the human love we have for each other, the love of use adds to it the acknowledgment that every love is a faint reflection of love’s finality in God. For Augustine, the love manifest in and by the ecclesia—which, as an ideal form, he held to be present seminally in every human society—is the highest love that humans possess for each other simply because it is the only love that is also self-consciously directed to the final cause of our being; in every other love and, therefore, in every other suffering, we conceal or even sever the thread that binds us to God. The members of the ecclesia, then, habitually seek to turn virtuous acts of doing things for the sake of each other into spiritual acts of being for the sake of each other, the former requiring a part, the latter the whole, of themselves. But how can there be a society so thoroughly and self-consciously founded on self-sacrifice? How can any society maintain such a psychological and spiritual tension? How can such a society last? 22

The Current Persecution of Love and Suffering

Throughout the modern age, philosophers and scientists have looked forward to and, since the nineteenth century, actively planned for the day when science, under the rubric of medicine and behavioral psychology, would have the capacity to eradicate suffering from the human condition. 23 In our present time, the technocratic systems on which we have become dependent for carrying out virtually all of our business and social communication, and which have gained the ascendency in critical areas of public policy, are aggressively implementing agendas that have, as their explicit goal, the eradication of suffering in all parts of the world. 24 Apropos of our theme in this essay, such a plan, if indeed it is as universal as it claims to be, must persecute 25 suffering all the way to its natural presence in human acts and the means and ends that underly them as their formal structure. It must, that is, somehow eradicate not only natural but supernatural human impulses and desires—the same impulses that ancient philosophers and theologians believed to be the vital forces behind the proximate and remote ends of moral actions—by abolishing the time and space in which alone they can be expressed. The vital energy of our loves, especially those that are most intense, must be rerouted to other organic mechanisms that allow for nothing but simple cause and effect relations. Relations of means and ends, consequently, must be replaced by relations of stimulus and response that are normally found only at the lowest animal level—that is, in organisms whose primitive structures, while totally lacking self-consciousness, nonetheless possess aggressive and efficient powers for propagating their own species. This means, of course, that no time or space would be left for either ecclesial or mystical acts of love and suffering. In an instructive irony, this secular plan, by eliminating the conditions for attaining the highest or final cause of human existence, can arrive only at the lowest or material cause. There can be no middle place, for that would be the natural condition of human acts, the time and space for which is always open to being contracted for one of two agendas: the cultivation of the superhuman love of religion or the enforcement of the subhuman desire of the viral algorithm.

A replica of Man at the Crossroads. The original painting was a fresco by Diego Rivera in New York City that was destroyed in 1933 before its completion.

Given that, in the modern age, the “hard” sciences have eliminated teleology from the legitimate concerns of research, it should not be surprising that the “soft” social sciences have imitated them by seeking to eliminate teleology in human acts, a plan that, by the reckoning of ancient teleology, must eventually arrive at collapsing the time required for willing the end as a good, deliberating on and choosing the means in a virtuous manner, and, finally, enjoying the end in one’s possession. Accordingly, just as the natural sciences have reduced the manifest teleology in nature to the bare material mechanism of cause and effect, so the social sciences have reduced the rich teleology of human intentions to the simple dichotomy of doing “this or that.” Finally, as physics has done away with metaphysics and theology, so behavioral psychology has done away with ethics and moral theology—and all ostensibly for the sake of control . Again, without suffering, there can be no natural or supernatural love; the human will at best know only a kind of primitive affection for the correct functioning of a mechanism that is not human but infrahuman, a microbial or viral sort of life.

But we have not yet followed the secular plan to its end, for we have not mentioned its intentions with respect to that particular suffering one feels in love itself—namely, the privation of the beloved object. As we mentioned above, nothing moves at all except insofar as it suffers the privation of the end that it desires. Is the secular eradication of suffering meant to go this far? And if so, must it not work against itself by eliminating, in the process, the possibility of any human motion, even the most primitive? Such an end is, in fact, impossible, but neither is it desirable, for while even this last suffering is despised, it must be kept alive if there is to be anything left at all of the human being—and, by implication, of other animals and even plants—that can be controlled—and control is what passes for the essential nature of the algorithm once made independent of immediate human guidance. 26 For this reason, then, the social engineers’ 27 desire to control suffering must be greater than their desire to annihilate it. But how can human beings ever be tempted to submit to such a diminution of their natural expansiveness of mind and will? An oft-quoted passage from Dostoyevsky’s Brothers Karamazov , in the part known as “The Grand Inquisitor,” may provide a plausible response: “In the end they will lay down their freedom at our feet and say: ‘Make us your slaves, if only you will feed us!’” 28 Accordingly, from Dostoyevsky’s traditionally religious perspective, the failure in the secular plan is not primarily one of reason but of intention; it is a failure of the will as manifest in its potential to love something higher than, and incommensurable with, itself. Most religions hold that we naturally love what is beyond our nature to attain, but they also hold that this love can only be satisfied supernaturally . The testimony of the martyr, as we have seen, is possible only with respect to the second and not to the first end—that is, to our supernatural and not to our natural end. But even so, it must presuppose our desire for the first end, for it is not something added, as if it were an alien influence, but rather something that perfects from within, working with what already is to make something that will be. If there is indeed such desire—and religion has testified to its existence for millennia—it must be directed beyond our human nature, and there must be an intuitive knowledge that our natural end is not our final end. Indeed, because the transcendental end is present seminally in the love we have for it, our work to achieve it will take the form of a return to it. The members of the ecclesia bear witness to each other of that end and the open field of divine life it implies. But at the same time, this gift of love, so long as we remain in our natural state, will always entail the burden of privation. Human community, therefore, must always itself be a burden, but a burden by design.

Beyond the question of whether the power of self-sacrifice, the sheer seminal energy of its eruption into the relative bonds of society, should be allowed to be expressed , there is the more pressing question, given our present circumstances, of whether it can be suppressed —whether, that is, the natural and even supernatural intensity in us can be extinguished or perpetually kept in check, even by a mechanism whose power and extent now encompass the entire world. Perhaps these questions cannot be answered as a practical matter but only as a matter of faith—that is, by an appeal to principle. But there is a practical question that might be answered: Is such a thing being attempted in the present time? 29 If so, then more questions arise, such as, What must we do to stop it? But here we must ask who “we” are, and this leads to more doubts regarding the means—that is, who will take the actions necessary to preserve a humanity the essentials for which we are close to forgetting? These questions can lead to an intolerable vertigo. But if one answers the question of whether the plan is actually happening in the affirmative, then it seems that the only place to look is to a broader plan—namely, the providence of God. It is that plan, after all, that established the twofold end of humanity, and that alone, therefore, can remind us of the great power that is present in every human act of using the means to attain the end. As long as one can still imagine the radical intensity of love and suffering that can be found in self-sacrificial acts of being for the sake of another, then one will always have access to the door that leads out of the prison of mere determinism and brute material causality and toward the wide field of the divine life.

BROWSE THE TABLE OF CONTENTS AND BUY THE PRINT EDITION IN WHICH THIS ARTICLE IS FEATURED

Renovatio is free to read online, but you can support our work by buying the print edition or making a donation.

- 1 Adam Kirsch, “Looking Forward to the End of Humanity,” Wall Street Journal , June 20, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/looking-forward-to-the-end-of-humanity-11592625661 . In order to stress the public awareness of the information provided in this part of the paper, I have chosen all the quotations from popular online media sources.

- 2 C. S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man: How Education Develops Man’s Sense of Morality (New York: MacMillan Publishing Co., 1947), 77.

- 3 “Transhumanism promises that death can be conquered physically, not just spiritually; and the movement has the support of people with the financial resources to make it happen, if anyone can.” Kirsch, “Looking Forward to the End of Humanity.”

- 4 Lewis, Abolition of Man , 78: “My point is that those who stand outside all judgements of value cannot have any ground for preferring one of their own impulses to another except the emotional strength of that impulse.” Lewis’s pivotal analysis of humans choosing to be more than human is the key to understanding the paradoxes involved in the motives of “scientific planners,” i.e., scientists and technocrats who, being in positions of great power, seek absolute control over human behavior.

- 5 Considered from the perspective of the use of algorithms to manipulate human behavior, every online platform is some form of social media platform.

- 6 Michael Matheson Miller, “Social Media—What a Bummer,” Law and Liberty , October 22, 2018, https://lawliberty.org/social-media-what-a-bummer/ . The article quoted is about Jaron Lanier’s book, Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now .

- 7 Paul Solman, “Jaron Lanier’s Argument for Getting Off Facebook,” PBS, May 17, 2018, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/economy/making-sense/jaron-laniers-argument-for-getting-off-facebook .

- 8 Tom Rassmussen, “When Did Social Media Steal Our Free Will?” i-D, November 30, 2016, https://i-d.vice.com/en_uk/article/8xg54v/when-did-social-media-steal-our-free-will .

- 9 Wikipedia, s.v. “Social Media and Suicide,” last edited September 27, 2020, 21:24, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_media_and_suicide .

- 10 Miller, “Social Media—What a Bummer.”

- 11 “[Saul] Smilansky advocates a view he calls illusionism—the belief that free will is indeed an illusion, but one that society must defend. The idea of determinism, and the facts supporting it, must be kept confined within the ivory tower. Only the initiated, behind those walls, should dare to, as he put it to me, ‘look the dark truth in the face.’ Smilansky says he realizes that there is something drastic, even terrible, about this idea—but if the choice is between the true and the good, then for the sake of society, the true must go.” Stephen Cave, “There’s No Such Thing as Free Will. But We’re Better Off Believing in It Anyway,” The Atlantic (June 2016), https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/06/theres-no-such-thing-as-free-will/480750/.

- 12 De libero arbitrio , the title of an influential book by Augustine of Hippo.

- 13 Summa Theologiae , pt. I, question 6, art. 1.

- 14 “A thing cannot be ordained to any end unless the thing itself is known, together with the end to which it is ordained. Hence, there must be a knowledge of natural things in the divine intellect from which the origin and the order of nature come. The Psalmist suggests this proof when he says: ‘He that formed the eye, doth he not consider?’ (Psalms 93:9); for, as Rabbi Moses [Maimonides] points out, it is as if the Psalmist had said: ‘Does He not consider the nature of the eye—who has made it to be proportioned to its end, which is its act of seeing?’” Aquinas, Disputed Questions on Truth , question 2, art. 3.

- 15 Respectively, the cardinal virtues of prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance, and the theological virtues of faith, hope, and love.

- 16 See William Arndt and Felix Gingrich, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979), 633.

- 17 See the first listing for pasco in G. W. H. Lampe, A Patristic Greek Lexicon (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), 1049: “A. suffer ; 1. in particular of martyrs.”

- 18 I do not mean to imply that sacrificial suffering for the sake of God, or even “a god,” originated with Christianity. It is appropriate, nonetheless, to point out the unique meaning that it acquired in light of Christ’s crucifixion and the doctrinal implications over time of the victims of the persecutions in the early church.

- 19 The soldier does indeed give his life for the sake of his country or community, but though he may be honored once he returns home, his may not be a welcome presence amid the daily affairs of the society for whose good he volunteered to make himself the means. On the contrary, the witness to war that he bears will make him seem a danger to the peaceful order of societal relations that, absorbed as they are with the parts, cannot, as he did, bear the weight of the whole.

- 20 In classical Greek, the word signified “a regularly summoned political body,” or, in general, an “assemblage, gathering, meeting.” With the advent of Christianity, it had several related meanings, e.g., “The Christian church or congregation,” “the church or congregation as the totality of Christians living in one place,” or the very broad sense that I am suggesting here: “the church universal, to which all believers belong.” Arndt and Gingrich, Greek-English Lexicon , 240–241.

- 21 From the Greek anachoreo (“to withdraw, retire”): “one that renounces the world to live in seclusion usually for religious reasons.” Philip B. Gove, ed., Webster’s Third New International Dictionary (Springfield, MA: G. & C. Merriam, 1961).

- 22 See Lewis, Abolition of Man , 42–44, for a penetrating discussion of modern society’s deliberate marginalization of heroic self-sacrifice.

- 23 “David Pearce, author of The Hedonistic Imperative , suggests that one day the assumption that emotional pain is indispensable may sound just as quaint. He believes that no pain, physical or emotional, is necessary. On the contrary, Pearce argues that we should strive to ‘eradicate suffering in all sentient life’—a project which he describes as ‘technically feasible’ thanks to genetic engineering and nanotechnology, and ‘ethically mandatory’ on utilitarian grounds.” Katherine Power, “The End of Suffering,” Philosophy Now , https://philosophynow.org/issues/56/The_End_of_Suffering . “‘We need,’ [Sam] Harris told me, ‘to know what are the levers we can pull as a society to encourage people to be the best version of themselves they can be.’” Cave, “There’s No Such Thing as Free Will.”

- 24 Contemporary global governance is organized around an odd pairing: care and control. On the one hand, much of global governance is designed to reduce human suffering and improve human flourishing, with the important caveat that individuals should be allowed to decide for themselves how they want to live their lives. On the other hand, these global practices of care are also entangled with acts of control.... Drawing on our moral intuitions, I argue that paternalism is the attempt by one actor to substitute his judgment for another actor’s on the grounds that such an imposition will improve the welfare of the target actor. After discussing and defending this definition, I note how our unease with paternalism seems to grow as we scale up from the interpersonal to the international, which I argue owes to the evaporation of community and equality. Michael Barnett, “Paternalism and Global Governance,” Abstract, Social Philosophy and Policy 32, no. 1 (Fall 2015): 216–243, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/social-philosophy-and-policy/article/paternalism-and-global-governance/F68F99C24B88F669D1677C1D267A67FC .

- 25 Compare the meanings of the Latin root of this word, persequor : to follow constantly, follow after, pursue; to press upon, chase; to pursue hostilely, punish; to prosecute judicially, and so on.

- 26 Sometimes, early twentieth-century intellectual historians can sum up the modern project more clearly and more powerfully, especially when they were “true believers,” than scholars and scientists writing in the last fifty years. A splendid example was Carl L. Becker, who wrote in The Heavenly City of the Eighteenth-Century Philosophers (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1965), 16–18. Accepting the fact as given, we observe it, experiment with it, verify it, classify it, measure it if possible, and reason about it as little as may be. The questions we ask are “What?” and “How?” What are the facts and how are they related? If sometimes, in a moment of absent-mindedness or idle diversion, we ask the question “Why?” the answer escapes us. Our supreme object is to measure and master the world rather than to understand it .... Since our supreme object is to measure and master the world, we can make relatively little use of theology, philosophy, and deductive logic—the three stately entrance ways to knowledge erected in the Middle Ages. In the course of eight centuries these disciplines have fallen from their high estate, and in their place we have enthroned history, science, and the technique of observation and measurement.... No respectable historian any longer harbors ulterior motives; and one who should surreptitiously introduce the gloss of a transcendent interpretation into the human story would deserve to be called a philosopher and straightway lose his reputation as a scholar. [Emphasis added]

- 27 This term continues to be used today to describe a wide range of social and physical scientists. A famous example of its use in the mid-twentieth century is in the following passage from Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World Revisited : “‘The challenge of social engineering in our time,’ writes an enthusiastic advocate of this new science, ‘is like the challenge of technical engineering fifty years ago. If the first half of the twentieth century was the era of the technical engineers, the second half may well be the era of the social engineers’—and the twenty-first century, I suppose, will be the era of World Controllers, the scientific caste system and Brave New World.... The future dictator’s subjects will be painlessly regimented by a corps of highly trained social engineers.” Brave New World and Brave New World Revisited (New York: Harper Collins, 1965), 22.

- 28 See Joseph Pieper’s 1972 discussion of the modern technocratic state and its formidable threat to free societies in his essay, “The Art of Not Yielding to Despair,” in Problems of Modern Faith: Essays and Addresses (Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press), 175–191. Besides Dostoyevsky, he quotes other authors who display an astounding prescience in this regard.

- 29 See Pieper. In 1972, it was admitted openly by scholars across Europe and America.

Republish Instructions

Please wait while we process your request

Sacrifice Essay Writing Guide

Published: 28th Feb 2019 | Last Updated: 31st Dec 2020 | Views: 51748

Academic writing

Essay paper writing

Sacrifice is a phenomenon that is largely lacking in modern society. In the era of consumer philosophy and selfish goals, people tend to forget about acts of kindness that bring not material but moral satisfaction.

It is important to draw the attention of schoolchildren and students to a topic of sacrifice by assigning them to write academic papers on this topic. Young people can express their views and share experiences regarding parental unconditional love, spiritual growth through sacrifice, and examples of sacrificing in family and social relations.

If you are looking through this article right now, you probably have to perform a similar task. If this is the case, we recommend reading the whole article as you will surely find some useful tips on how to write about sacrifice.

Sacrifice essay topics ideas

Got lost among essay ideas? Check out the list of the best ones to make a final choice:

- Parents’ sacrifice essay

- “My sacrifice” essay

- Essay on whether or not you need to sacrifice for love

- Essay about sacrifice in love and when it becomes unhealthy

- Essay about family sacrifice

- Essay about love and sacrifice in literary works

- Reasons for self-sacrifice essay

- “Sacrifice and bliss” essay

- Essay on importance of self-sacrifice in different cultures

- Essay about making sacrifices to better the world

- “Sacrifice of a teacher” essay

- Human sacrifice essay

- “Importance of sacrifice” essay

- Ultimate sacrifice essay

Topic ideas for informative essay on sacrifice

Writing an informative essay about making sacrifices, consider focusing on one of the following:

- Different kinds of sacrifices that people make

- “What is sacrifice?” essay

- Self-sacrificing personality type

- Ritual sacrifice essay

- Sacrificial moral dilemmas

- “What does sacrifice mean?” essay

- Chronic self-sacrifice and its influence on mental health

- Essay about mothers’ sacrifice

- Soldiers’ sacrifice essay

- Essay on sacrifice definition and etymology

- “Sacrifice in sport” essay

How to write essays on sacrifice?

The majority of students have to write essays on a regular basis. The main thing is not just to write some information on the topic in question but also to make it interesting and attract the attention of a potential reader starting from the first sentence. We have prepared all the useful information on essay writing so that you can craft a decent paper.

The following details should be taken into account while writing an essay about sacrifice:

- The topicality of the problem under consideration. The issues raised should be relevant to the modern world or interesting if you are writing about a history of the subject.

- Personal opinion. You will need to explain your stance on the problem and back it up with information you have found in the literary sources.

- Small volume. There are no strict boundaries when it comes to the length of an essay, but 2-5 pages of text will likely be enough. Ask your professor about the word limit or simply request a rubric if you aren’t sure.

- Narrow focus. Only one issue or problem may be considered within the framework of the essay. There cannot be many different topics or ideas discussed within one assignment as you will not be able to cover any of them properly.

Sacrifice essay outline

In general, the essay has quite a specific structure:

- Sacrifice essay introduction. This part should set the mood of the whole paper, bring the reader’s attention to the issue under consideration, and consequently prompt him or her to read the text to the end. The most important aspect of intro is a thesis statement, which bears the main idea you are going to discuss.

- The main part. Here, it is necessary to elaborate on the points put forward in a thesis statement using factual information found in credible sources. However, you should not operate with facts alone – add your analysis of what you have read and address the contradictions in sources if any. Please note that you need to devote at least one paragraph to each point made in the thesis to effectively cover it.

- By summarizing what has been said in the main part, you will draw a general sacrifice essay conclusion. If the goal of the introduction is to attract attention, then that of the conclusion is to ensure integrity of the overall paper and leave no doubts about the legitimacy or viability of the ideas expressed in the body of the paper. How to wrap up an essay about sacrifice so that your reader has a good impression? Leave him or her some food for thought!

Brainstorming sacrifice essay titles

The last thing you need to do after you are done with your paper is create a good title for a sacrifice essay. At this point, you will already know the subject under the research perfectly, which will make it easier to come up with a short title that will show what exactly you have reviewed in the paper. Use your thesis statement to guide yourself, and think about some common phrases people use when talking about the topic to rework them into your title.

How to write a sacrifice essay: Best tips

- Speak you mind. This particular type of writing gives you an opportunity to say what you really think about the topic. Make your voice heard in your sacrifice essay!

- Mind your language. It’s very important to find a balance as your language should be neither too scientific nor too elevated. Slang words are not acceptable as well – try writing as if you are having a conversation with your professor and are trying to sound convincing.

- Spend some time researching. Whether it’s a sacrifice research paper or an essay, you need to focus a lot of your attention on finding credible sources. So, conduct some research on sacrifice topic on the Web and try reading journal articles rather than news or blog posts.

- Proofread your writing. After writing the first draft, let it rest for a day or two and then proofread it with a fresh eye. This will help you spot more mistakes, inconsistencies, or lack of transition between ideas and paragraphs.

- Mind the formatting. A properly formatted essay will probably win you a good impression. Ask your teacher what style of formatting you have to stick to and follow all the requirements to the letter.

Writing a narrative essay on sacrifice

A narrative essay about sacrifice is a story about some event experienced by a writer or another person. A narrative essay is usually written in the artistic style. This means that it is necessary to use all the diversity of the English vocabulary. You can add conversational elements and descriptions to paint a clearer picture of what is going on to the reader.

In order to write a high-quality narrative essay, you need to follow these simple steps:

- Select the event or a person which you are going to write about;

- Think about the mood and the main idea of the future story;

- Recall in memory all the necessary details about this story and write them down in bullet points to use later;

- Create a well-detailed outline. Make sure it includes introduction (background), main part, culmination, and conclusion.

- Use the dialogue or separate replicas, elements of description, etc., which will help you to present the course of events in a more realistic way and humanize the characters.

If you are writing a narrative essay on personal sacrifice, be careful not to overshare. You need to understand how much information you professor is comfortable with you sharing, and it is best to ask them what is acceptable and what is not before you proceed. If you are narrating a story of your friend or relative, make sure you have gotten their permission to do so, and, preferably, inform your professor that you did. Check some samples of a narrative essay about a family member sacrifice to see how such information can be conveyed.

There is a bunch of different topics pertaining to sacrifice that you might write an essay on. Whatever the topic is, you do not have to worry. It is quite easy to write a top-notch essay if you have sufficient information and know the basic rules of writing academic papers.

Your email address will not be published / Required fields are marked *

Order an essay!

Fill out the order form

Make a secure payment

Receive your order by email

Dissertation writing services

Good Thesis Topics and Ideas for Ph.D. and Master Students

Without any doubt, a thesis is the most important paper in the academic life of a student or young researcher. Many of them may be a bit afraid of the scope of work that awaits or the inability to…

4th Sep 2018

Business paper writing

Examples of job application letters

Job application letters (they're also called 'cover letters') are sent or uploaded with resumes when it comes to applying for jobs. Without a great application letter chances that your…

4th Nov 2016

Resume services

Advantages and Disadvantages of Temporary Employment

So you have left your job without a new job to go to. You haven’t done this before, your funds are starting to get rather low and you need a short term job right this very minute. Or you are…

4th Jun 2018

Calculate your price

Number of pages:

Get your project done perfectly

Professional writing service

Reset password

We’ve sent you an email containing a link that will allow you to reset your password for the next 24 hours.

Please check your spam folder if the email doesn’t appear within a few minutes.

Brill | Nijhoff

Brill | Wageningen Academic

Brill Germany / Austria

Böhlau

Brill | Fink

Brill | mentis

Brill | Schöningh

Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht

V&R unipress

Open Access

Open Access for Authors

Transformative Agreements

Open Access and Research Funding

Open Access for Librarians

Open Access for Academic Societies

Discover Brill’s Open Access Content

Organization

Stay updated

Corporate Social Responsiblity

Investor Relations

Policies, rights & permissions

Review a Brill Book

Author Portal

How to publish with Brill: Files & Guides

Fonts, Scripts and Unicode

Publication Ethics & COPE Compliance

Data Sharing Policy

Brill MyBook

Ordering from Brill

Author Newsletter

Piracy Reporting Form

Sales Managers and Sales Contacts

Ordering From Brill

Titles No Longer Published by Brill

Catalogs, Flyers and Price Lists

E-Book Collections Title Lists and MARC Records

How to Manage your Online Holdings

LibLynx Access Management

Discovery Services

KBART Files

MARC Records

Online User and Order Help

Rights and Permissions

Latest Key Figures

Latest Financial Press Releases and Reports

Annual General Meeting of Shareholders

Share Information

Specialty Products

Press and Reviews

Share link with colleague or librarian

Stay informed about this journal!

- Get New Issue Alerts

- Get Advance Article alerts

- Get Citation Alerts

Introduction: Sacrifice and Self-Sacrifice: A Religious Concept under Transformation

Sacrifice, originally a religious-cultic concept, has become highly secularized and used in various instances for different social phenomena. The current issue puts forward a selection of papers that offer insights into sacrifice and self-sacrifice and focus on the process of transformation of the sacrificial individual. Three main axes put the concrete papers into a dialogue with one another: first, there is the philosophical-theological and gender reflection of the experience of the paradigmatic sacrificial story of the western tradition, i.e., the Akedah (Gen 22); second, the existential-phenomenological interpretation of self-sacrifice in the secular world which nevertheless aims to reveal a higher good – Freedom, Love, or the Good; third, the gender and feminist reflection of the motherly sacrifice of childbirth both in the religious-cultic context and in the secular context which presents childbirth both as a moment of autonomy loss and submission and a moment of women self-emancipation.

Sacrifice is a troublesome concept that brings various pre-understandings and plenty of biases to the scholarly debate; however, to cover the whole spectrum of its possible meanings would go far beyond the possibilities of the current issue. The goal of this introduction is to outline the basic contours of sacrificial discourses included within the issue and to help the reader navigate these particular contributions. The term sacrifice developed in the cultic-religious environment, but it became secularised over time. It is no longer obvious in general usage that sacrifice has a religious origin. The secularisation process, together with the neo-liberal understanding of the self and its agency, brought about different ways of talking about sacrifice, including ways of discussing “sacrificial acting” without using the term sacrifice at all. 1 However, a conscious avoidance of the term, which has become for various reasons popular in current philosophical, theological and socio-political debates, does not change the fact that the Jewish and Christian roots of our culture and civilization are built on the logic of sacrifice. 2

The basic understanding of sacrifice (be it secular or religious) is the economy of exchange – I give up something to receive something (ideally more valuable) in return. This is the general form (despite all the potential nuances) 3 that is depicted by anthropologists of religion and theorists of sacrifice, such as Robertson Smith, Bataille, Burkett, Hubert and Mauss, 4 and with which they introduce ways that people communicated with their deity, the so-called do ut des model. Another influential theory of sacrifice, which is formulated from the perspective of social theory of violence and religion, is brought by the French literary theorist and social anthropologist René Girard. 5 Girard is convinced that sacrifice developed as a function of society needing to rid itself of accumulated violence and therefore generating the so-called sacrificial scapegoat (typically a foreigner, a captive or some other person incompatible with the community). Sacrifice, in Girard’s system, is a ritual which includes an “appointed scapegoat” who takes upon herself or himself all the sins, sicknesses, and impurities of the whole community to restore peace. The ritual includes chasing away and/or killing the scapegoat during an ecstatic cultic ritual. The scapegoat is deified after death and is therefore able to exercise magical atoning power over the community. The cycle repeats itself when the community needs another reconciliation process. 6

The present issue, even though its contributions refer here and there to the “economy of exchange” or “violence as a social phenomenon which is to be channelled away”, is based, however, on the sacrificial/self-sacrificial experience of the individual. A leitmotif running through almost all the articles is the story of the Binding of Isaac , the so-called Akedah in Gen 22. The most prominent interpretation referenced in the articles is of course that of the Danish master of existentialism Søren Kierkegaard, along with reflections on Kierkegaard by Franz Kafka, Jan Patočka or Jacques Derrida; the articles seek to embrace the efforts of various philosophers and theologians to depict the transformation of the self in the liminal situation of sacrifice. Special attention is paid to questions of gender. Among the authors who notice the importance of gender within the sacrificial discourse are Julia Kristeva, Judith Butler and Yvonne Sherwood. What is the role of gender in sacrifice? Does the experience of the feminine sacrificial self differ from the masculine sacrificial self? Is there any unique feminine sacrifice which is totally untranslatable, for example, childbirth and the experience of motherhood in the broader sense? Does the role of victim fall to women more often than to men? And is our society irredeemably built on sacrifice? The current issue is woven from these and other questions related to sacrifice and the transformation of the self within the process of self-sacrifice.

Despite the diversity of the contributions, there are significant links which bind them together. One of the most important links is undoubtedly the emphasis on the moment of transformation of the self within the sacrificial experience. The order of contributions follows a twofold logic: first, the chronological order and, second, the level of engagement of particular papers with the question of gender.

Anna Sjöberg, in her article “Other Abrahams: Sacrificing Faith. Augustine – Kierkegaard – Kafka”, explores sacrifice as a function of what she calls “the circle of faith”, including call (from God) and act (human response). Looking at Augustine, Kierkegaard and Kafka, she addresses three different approaches to the circle of faith and the role of sacrifice contained therein. Augustine, she believes, sacrifices those outside the circle of faith (unbelievers). In Kierkegaard, sacrifice stands for the internal struggle of those who do not accept religion in the aesthetic or ethical sense, a struggle which transforms them into solitary “knights of faith”. Kafka introduces doubt about the circle of faith in a highly secularised world, pointing out that not only our response but also the calling itself cannot be taken for granted. Victims of “sacrifice in service of faith” are to be found on all fronts, religious and non-religious alike. Sjöberg concludes: “If it is true that the circle of faith always demands a sacrifice in order to safeguard an interior space of faith, we all, believer and non-believer alike, find ourselves excluded from this interior perspective, sacrificed in order for the notion of faith to live on.”

Vivian Liska, in her contribution “Law and Sacrifice in Kafka and his Readers”, explores the relationship between the law, which is implicitly present and which penetrates all Kafka’s writings, and sacrifice, and asks if the law makes its subjects victims of sacrifice. Liska compares “important interpretations of Kafka’s relation to law and sacrifice, one by the contemporary Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben […], the other by the German-Jewish thinker Walter Benjamin […].” Agamben, similarly to the Apostle Paul, Liska observes, argues that the law is always oppressive and must be overcome by the messianic form of self-sacrifice. Liska notes that Benjamin compares Kafka’s interpretations of the law to the Haggadic narrations that complement the Halakhic orders. These Haggadic narrations then suggest the deferral of the law (and therefore also of sacrifice). To make her argument about Kafka’s ultimate deferral of sacrifice crystal clear, Liska appeals to Kafka’s “other Abrahams”, who invent anything conceivable to postpone endlessly the divine order. Liska concludes: “Kafka imagines another Abraham, however, one who engages in an ongoing conversation with God and his commandments, who would not depart for Mount Moriah intending to sacrifice his beloved son.”

Clarissa Breu, in her “Exposure of Violence”, approaches the ever-repeating story of the Binding of Isaac as a performative reading of the passage alongside Judith Butler’s and Giorgio Agamben’s theories of gesture. Sacrifice in Breu’s article plays a functional role within an inherently violent society. Breu suggests that “violence is not abolished in the Aqeda , but exposed and thereby questioned.” She focuses on the moment of interruption: “[H]e [Abraham] reached out his hand and took the knife to slay his son” (Gen 22:10). The sacrificial act is not completed, but neither it is negated. The question remains with us until today: What would have happened if the angel of God did not interrupt the sacrifice? Breu deliberately decides to put this question aside to focus rather on what we see happening in the text (and not on what we do not see). We see Abraham stretching out his hand but then yielding. We see God compelling but then interrupting. In the Girardian vein (used by Breu in another context), we observe sacrifice as a means of channeling away the accumulated violence. Breu concludes: “The Aqeda is an example of a restrained violent act that is first interrupted and then redirected.”

Esther and Richard Heinrich, in their article “Sacrifice and Obedience: Simon Weil on the Binding of Isaac”, focus on the relationship between sacrifice and unconditional obedience to God. They point out the importance of the “void” created by Abraham (in other words, by Abraham’s obedience towards God’s command) twice during the story and which provided space for God to give Abraham his son back. Abraham’s obedience is compared to the parallel story about Iphigenia in Aulis, in which Agamemnon’s disobedience (killing Artemis’s stag) not only brought misery upon the whole of Greece, but also culminated in his daughter Iphigenia being sacrificed. Violence is, in Weil’s system, understood as a political and not as a philosophical category. Despite the problematic nature of categories such as sacrifice and obedience in the current philosophical debates, Heinrich suggest that “Weil’s estimation of these conceptions as the very basics of moral acts could be read as a call for a kind of modesty, as a call not to put oneself above the world.”

Sandra Lehmann, in her contribution “Ways of Self-Transcendence: On Sacrifice for Nothing and Hyperbolic Ontology”, explores ways of transcending the category of Being in the extreme situation of self-sacrifice. Lehmann addresses the “concept of a transcendent Good and its impact on one’s attitude towards life.” She remarks that “[i]n the ancient version, the Good is beyond all things, both sensible and intelligible, and exceeds them. This is why it enables those orienting themselves towards it to also exceed their worldly self.” In her friendly polemic with Jan Patočka, Lehmann remarks that Patočka’s concept of sacrifice for nothing , that is, for nothing else but for pure Being in the sense of its ontological difference, is in fact too hollow to promise anything positive to turn to. Even if this “nothing” in Patočka’s system means freedom from the instrumentalization of human beings, it is, Lehmann claims, too little. What Lehmann offers instead is the idea of the hyperbolic ontology, in other words, “transcending oneself” for the sake of pure Good, based on antique philosophy.

Martin Koci, in his article “Almost for Nothing: The Question of Sacrifice in Jan Patočka”, offers a different interpretation of Patočka’s “sacrifice for nothing”. Koci is persuaded that the controversial and maybe somewhat misleading term “for nothing” is the best and in fact the only way to rescue Being from increasing instrumentalization and from misuse. If “there is nothing like sacrifice” (only utilization of human resources), then the elegant solution is, according to Koci, “sacrifice for nothing”. However, beyond defending the troublesome concept, Koci investigates Patočka’s oeuvre and notices two slightly different aspects of the “sacrifice for nothing”: first, the so-called “heroic sacrifice” (one could say the “active sacrifice”), which Koci illustrates with the figure of the Czech student who immolated himself in the protest against the Soviet occupation in 1968; second, the “kenotic/self-emptying sacrifice” (one could say the “more accepting sacrifice”), which, for Koci, is illustrated by the death of Jesus of Nazareth on the cross. To join these two aspects of “sacrifice for nothing”, Koci provides an example which is both heroic and kenotic, that of the sacrifice of a mother for her child.

René Rosfort, in his contribution entitled “Sacrificing Gender: Kierkegaard and the Traumatic Self”, enters a rather contested research field of “Kierkegaard and gender”. Rather than addressing the question of Kierkegaard’s misogyny, Rosfort instead investigates the role of gender in the key Kierkegaardian concept of “becoming Self”. He observes: “We are not simply free to choose who we are. Because of our gender we already are a self before we become a self. In becoming who we are we cannot escape what we are.” Following the complex dialectics of Kierkegaard’s self-denial and self-affirmation, Rosfort employs the same logic to discuss “sacrificing gender”. On the one hand, we have to “sacrifice” our gendered biases to embrace the universal and ethical self. On the other hand, to be true and loving human beings, we must embrace our gendered (that is, our human) self. Thus, Rosfort concludes: “To sacrifice gender is not and cannot be to cultivate an ungendered love. On the contrary, it is a radical love that sacrifices my sexual biases to make room for the individual otherness of gender differences that make me and other people the gendered selves that we are.”

Petr Vaškovic, in his account “Kierkegaard’s Existentialist Sacrifice”, asks whether the state of “reflective sorrow” (a phenomenon discussed in Kierkegaard’s Either/Or ), which entraps one in the aesthetic stage by cyclical self-interrogation and prevents any advancement towards the ethical and religious stages, is or is not gendered. Analysing Kierkegaard’s portrayal of two fictious female characters – Marie Beaumarchais and Donna Elvira – and his interpretation of their inner state, Vaškovic concludes that the gendered state of both characters demonstrates pre-Romantic conceptions of women’s role in society and gender essentialism, rather than a gendering of “reflective sorrow” itself. Similarly to Rosfort, Vaškovic is convinced that despite its clear misogynistic traces, Kierkegaard’s oeuvre is multi-layered with regard to gender-related questions. Furthermore, Vaškovic contends, Kierkegaard’s depiction of the state of reflective sorrow is highly influenced by his own experience of the break up with his fiancé Regine Olsen. Vaškovic is convinced that, after peeling away layers of context and other miscellaneous factors, the phenomenon of reflective sorrow proves to be gender neutral.

Caecile Varslev Pedersen, in her contribution “Mothers and Melancholia: Sacrifice in Søren Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling ”, juxtaposes four alternative interpretations of the Binding of Isaac that represent the image of the religious/fatherly love and four ways of weaning the infant that stand for the aesthetic/motherly love. Borrowing Freudian terminology, Pedersen points out that mourning is temporary and promises both transformation and a way forward (weaning of the infant), whereas melancholia is timeless and does not promise any advancement (Abraham’s loss of Isaac). Pedersen observes: “Motherly love is an image of a sacrifice that is only relative, and of a loss that is acknowledged so that a new beginning can ensue. Thus, the weaning images lead us to a story about sacrifice in Fear and Trembling that not only concerns pain, violence, and death, but also mourning, birth, transition, and mothering new possibilities.” Despite the hopeful image of positive and transformative motherly sacrifice, Pedersen fears that the predominant model of sacrifice in Kierkegaard’s oeuvre is the fatherly sacrifice which leaves the scar on one’s soul forever – that is, the self-sacrifice which is the prerequisite for becoming the “knight of faith”.

My own article, entitled “All the Rest Is Commentary: Being for the Other as the Way to Break the Sacrificial Logic”, compares the woman’s sacrifice in childbirth with what feminist scholars have labelled the “patriarchal sacrifice” in the story of the Binding of Isaac . I present both events as potentially self-emptying, transformative and identity-dividing moments that empower the individual to break the sacrificial logic constituting the roots of our Jewish and Christian society. Even if we deconstruct the gender stereotypes in the story of the Binding of Isaac , the sacrifice of childbirth remains undeniably gendered. However, thanks to the account of Julia Kristeva, who introduces the so-called Third Party (or the pre-oedipal father) into the otherwise enclosed and dialectical relationship of the mother and her child, we are invited to think of this utterly gendered sacrifice in a less gender-biased way.