Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Definition and Purpose of Abstracts

An abstract is a short summary of your (published or unpublished) research paper, usually about a paragraph (c. 6-7 sentences, 150-250 words) long. A well-written abstract serves multiple purposes:

- an abstract lets readers get the gist or essence of your paper or article quickly, in order to decide whether to read the full paper;

- an abstract prepares readers to follow the detailed information, analyses, and arguments in your full paper;

- and, later, an abstract helps readers remember key points from your paper.

It’s also worth remembering that search engines and bibliographic databases use abstracts, as well as the title, to identify key terms for indexing your published paper. So what you include in your abstract and in your title are crucial for helping other researchers find your paper or article.

If you are writing an abstract for a course paper, your professor may give you specific guidelines for what to include and how to organize your abstract. Similarly, academic journals often have specific requirements for abstracts. So in addition to following the advice on this page, you should be sure to look for and follow any guidelines from the course or journal you’re writing for.

The Contents of an Abstract

Abstracts contain most of the following kinds of information in brief form. The body of your paper will, of course, develop and explain these ideas much more fully. As you will see in the samples below, the proportion of your abstract that you devote to each kind of information—and the sequence of that information—will vary, depending on the nature and genre of the paper that you are summarizing in your abstract. And in some cases, some of this information is implied, rather than stated explicitly. The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , which is widely used in the social sciences, gives specific guidelines for what to include in the abstract for different kinds of papers—for empirical studies, literature reviews or meta-analyses, theoretical papers, methodological papers, and case studies.

Here are the typical kinds of information found in most abstracts:

- the context or background information for your research; the general topic under study; the specific topic of your research

- the central questions or statement of the problem your research addresses

- what’s already known about this question, what previous research has done or shown

- the main reason(s) , the exigency, the rationale , the goals for your research—Why is it important to address these questions? Are you, for example, examining a new topic? Why is that topic worth examining? Are you filling a gap in previous research? Applying new methods to take a fresh look at existing ideas or data? Resolving a dispute within the literature in your field? . . .

- your research and/or analytical methods

- your main findings , results , or arguments

- the significance or implications of your findings or arguments.

Your abstract should be intelligible on its own, without a reader’s having to read your entire paper. And in an abstract, you usually do not cite references—most of your abstract will describe what you have studied in your research and what you have found and what you argue in your paper. In the body of your paper, you will cite the specific literature that informs your research.

When to Write Your Abstract

Although you might be tempted to write your abstract first because it will appear as the very first part of your paper, it’s a good idea to wait to write your abstract until after you’ve drafted your full paper, so that you know what you’re summarizing.

What follows are some sample abstracts in published papers or articles, all written by faculty at UW-Madison who come from a variety of disciplines. We have annotated these samples to help you see the work that these authors are doing within their abstracts.

Choosing Verb Tenses within Your Abstract

The social science sample (Sample 1) below uses the present tense to describe general facts and interpretations that have been and are currently true, including the prevailing explanation for the social phenomenon under study. That abstract also uses the present tense to describe the methods, the findings, the arguments, and the implications of the findings from their new research study. The authors use the past tense to describe previous research.

The humanities sample (Sample 2) below uses the past tense to describe completed events in the past (the texts created in the pulp fiction industry in the 1970s and 80s) and uses the present tense to describe what is happening in those texts, to explain the significance or meaning of those texts, and to describe the arguments presented in the article.

The science samples (Samples 3 and 4) below use the past tense to describe what previous research studies have done and the research the authors have conducted, the methods they have followed, and what they have found. In their rationale or justification for their research (what remains to be done), they use the present tense. They also use the present tense to introduce their study (in Sample 3, “Here we report . . .”) and to explain the significance of their study (In Sample 3, This reprogramming . . . “provides a scalable cell source for. . .”).

Sample Abstract 1

From the social sciences.

Reporting new findings about the reasons for increasing economic homogamy among spouses

Gonalons-Pons, Pilar, and Christine R. Schwartz. “Trends in Economic Homogamy: Changes in Assortative Mating or the Division of Labor in Marriage?” Demography , vol. 54, no. 3, 2017, pp. 985-1005.

![research abstract template word “The growing economic resemblance of spouses has contributed to rising inequality by increasing the number of couples in which there are two high- or two low-earning partners. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the topic under study (the “economic resemblance of spouses”). This sentence also implies the question underlying this research study: what are the various causes—and the interrelationships among them—for this trend?] The dominant explanation for this trend is increased assortative mating. Previous research has primarily relied on cross-sectional data and thus has been unable to disentangle changes in assortative mating from changes in the division of spouses’ paid labor—a potentially key mechanism given the dramatic rise in wives’ labor supply. [Annotation for the previous two sentences: These next two sentences explain what previous research has demonstrated. By pointing out the limitations in the methods that were used in previous studies, they also provide a rationale for new research.] We use data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to decompose the increase in the correlation between spouses’ earnings and its contribution to inequality between 1970 and 2013 into parts due to (a) changes in assortative mating, and (b) changes in the division of paid labor. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The data, research and analytical methods used in this new study.] Contrary to what has often been assumed, the rise of economic homogamy and its contribution to inequality is largely attributable to changes in the division of paid labor rather than changes in sorting on earnings or earnings potential. Our findings indicate that the rise of economic homogamy cannot be explained by hypotheses centered on meeting and matching opportunities, and they show where in this process inequality is generated and where it is not.” (p. 985) [Annotation for the previous two sentences: The major findings from and implications and significance of this study.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-1.png)

Sample Abstract 2

From the humanities.

Analyzing underground pulp fiction publications in Tanzania, this article makes an argument about the cultural significance of those publications

Emily Callaci. “Street Textuality: Socialism, Masculinity, and Urban Belonging in Tanzania’s Pulp Fiction Publishing Industry, 1975-1985.” Comparative Studies in Society and History , vol. 59, no. 1, 2017, pp. 183-210.

![research abstract template word “From the mid-1970s through the mid-1980s, a network of young urban migrant men created an underground pulp fiction publishing industry in the city of Dar es Salaam. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the context for this research and announces the topic under study.] As texts that were produced in the underground economy of a city whose trajectory was increasingly charted outside of formalized planning and investment, these novellas reveal more than their narrative content alone. These texts were active components in the urban social worlds of the young men who produced them. They reveal a mode of urbanism otherwise obscured by narratives of decolonization, in which urban belonging was constituted less by national citizenship than by the construction of social networks, economic connections, and the crafting of reputations. This article argues that pulp fiction novellas of socialist era Dar es Salaam are artifacts of emergent forms of male sociability and mobility. In printing fictional stories about urban life on pilfered paper and ink, and distributing their texts through informal channels, these writers not only described urban communities, reputations, and networks, but also actually created them.” (p. 210) [Annotation for the previous sentences: The remaining sentences in this abstract interweave other essential information for an abstract for this article. The implied research questions: What do these texts mean? What is their historical and cultural significance, produced at this time, in this location, by these authors? The argument and the significance of this analysis in microcosm: these texts “reveal a mode or urbanism otherwise obscured . . .”; and “This article argues that pulp fiction novellas. . . .” This section also implies what previous historical research has obscured. And through the details in its argumentative claims, this section of the abstract implies the kinds of methods the author has used to interpret the novellas and the concepts under study (e.g., male sociability and mobility, urban communities, reputations, network. . . ).]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-2.png)

Sample Abstract/Summary 3

From the sciences.

Reporting a new method for reprogramming adult mouse fibroblasts into induced cardiac progenitor cells

Lalit, Pratik A., Max R. Salick, Daryl O. Nelson, Jayne M. Squirrell, Christina M. Shafer, Neel G. Patel, Imaan Saeed, Eric G. Schmuck, Yogananda S. Markandeya, Rachel Wong, Martin R. Lea, Kevin W. Eliceiri, Timothy A. Hacker, Wendy C. Crone, Michael Kyba, Daniel J. Garry, Ron Stewart, James A. Thomson, Karen M. Downs, Gary E. Lyons, and Timothy J. Kamp. “Lineage Reprogramming of Fibroblasts into Proliferative Induced Cardiac Progenitor Cells by Defined Factors.” Cell Stem Cell , vol. 18, 2016, pp. 354-367.

![research abstract template word “Several studies have reported reprogramming of fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes; however, reprogramming into proliferative induced cardiac progenitor cells (iCPCs) remains to be accomplished. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence announces the topic under study, summarizes what’s already known or been accomplished in previous research, and signals the rationale and goals are for the new research and the problem that the new research solves: How can researchers reprogram fibroblasts into iCPCs?] Here we report that a combination of 11 or 5 cardiac factors along with canonical Wnt and JAK/STAT signaling reprogrammed adult mouse cardiac, lung, and tail tip fibroblasts into iCPCs. The iCPCs were cardiac mesoderm-restricted progenitors that could be expanded extensively while maintaining multipo-tency to differentiate into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells in vitro. Moreover, iCPCs injected into the cardiac crescent of mouse embryos differentiated into cardiomyocytes. iCPCs transplanted into the post-myocardial infarction mouse heart improved survival and differentiated into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells. [Annotation for the previous four sentences: The methods the researchers developed to achieve their goal and a description of the results.] Lineage reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs provides a scalable cell source for drug discovery, disease modeling, and cardiac regenerative therapy.” (p. 354) [Annotation for the previous sentence: The significance or implications—for drug discovery, disease modeling, and therapy—of this reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-3.png)

Sample Abstract 4, a Structured Abstract

Reporting results about the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis, from a rigorously controlled study

Note: This journal requires authors to organize their abstract into four specific sections, with strict word limits. Because the headings for this structured abstract are self-explanatory, we have chosen not to add annotations to this sample abstract.

Wald, Ellen R., David Nash, and Jens Eickhoff. “Effectiveness of Amoxicillin/Clavulanate Potassium in the Treatment of Acute Bacterial Sinusitis in Children.” Pediatrics , vol. 124, no. 1, 2009, pp. 9-15.

“OBJECTIVE: The role of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis (ABS) in children is controversial. The purpose of this study was to determine the effectiveness of high-dose amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate in the treatment of children diagnosed with ABS.

METHODS : This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Children 1 to 10 years of age with a clinical presentation compatible with ABS were eligible for participation. Patients were stratified according to age (<6 or ≥6 years) and clinical severity and randomly assigned to receive either amoxicillin (90 mg/kg) with potassium clavulanate (6.4 mg/kg) or placebo. A symptom survey was performed on days 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 20, and 30. Patients were examined on day 14. Children’s conditions were rated as cured, improved, or failed according to scoring rules.

RESULTS: Two thousand one hundred thirty-five children with respiratory complaints were screened for enrollment; 139 (6.5%) had ABS. Fifty-eight patients were enrolled, and 56 were randomly assigned. The mean age was 6630 months. Fifty (89%) patients presented with persistent symptoms, and 6 (11%) presented with nonpersistent symptoms. In 24 (43%) children, the illness was classified as mild, whereas in the remaining 32 (57%) children it was severe. Of the 28 children who received the antibiotic, 14 (50%) were cured, 4 (14%) were improved, 4(14%) experienced treatment failure, and 6 (21%) withdrew. Of the 28children who received placebo, 4 (14%) were cured, 5 (18%) improved, and 19 (68%) experienced treatment failure. Children receiving the antibiotic were more likely to be cured (50% vs 14%) and less likely to have treatment failure (14% vs 68%) than children receiving the placebo.

CONCLUSIONS : ABS is a common complication of viral upper respiratory infections. Amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate results in significantly more cures and fewer failures than placebo, according to parental report of time to resolution.” (9)

Some Excellent Advice about Writing Abstracts for Basic Science Research Papers, by Professor Adriano Aguzzi from the Institute of Neuropathology at the University of Zurich:

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Academic Programs within an Undergraduate College

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Diversity Statements

Professional Emails

Advice for Students Writing a Professional Email

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

APA Formatting and Style (7th ed.)

- What's New in the 7th ed.?

- Principles of Plagiarism: An Overview

- Basic Paper Formatting

- Basic Paper Elements

- Punctuation, Capitalization, Abbreviations, Apostrophes, Numbers, Plurals

- Tables and Figures

- Powerpoint Presentations

- Reference Page Format

- Periodicals (Journals, Magazines, Newspapers)

- Books and Reference Works

- Webpage on a Website

- Discussion Post

- Company Information & SWOT Analyses

- Dissertations or Theses

- ChatGPT and other AI Large Language Models

- Online Images

- Online Video

- Computer Software and Mobile Apps

- Missing Information

- Two Authors

- Three or More Authors

- Group Authors

- Missing Author

- Chat GPT and other AI Large Language Models

- Secondary Sources

- Block Quotations

- Fillable Template and Sample Paper

- Government Documents and Legal Materials

- APA Style 7th ed. Tutorials

- Additional APA 7th Resources

- Grammarly - your writing assistant

- Writing Center - Writing Skills This link opens in a new window

- Brainfuse Online Tutoring

APA 7th ed. Fillable Word Template and Sample Paper

- APA 7th ed. Template Download this Word document, fill out the title page and get writing!

- Sample Paper APA 7th ed. Our APA sample paper shows you how to format the main parts of a basic research paper.

- APA 7th Sample Papers from Purdue Owl

- << Previous: Block Quotations

- Next: Government Documents and Legal Materials >>

- Last Updated: Oct 14, 2024 1:11 PM

- URL: https://national.libguides.com/apa_7th

- Page number

- Running head

- Table of Contents

- Academic Success

Abstract Page in APA Format: How to Write Using Microsoft Word

This guide shows you how to create an abstract page in APA format using Microsoft Word.

The abstract plays a crucial role in your academic paper—whether you're working on a research paper, thesis, review, case study, report, or essay.

The abstract plays a significant role in your work, giving readers a quick glimpse of what your work is about and helping them decide if they want to read more.

What is an abstract?

Think of an abstract as a summary of your entire paper. It covers the main points of your work, like its purpose, methods, results, and conclusions.

See what makes a good abstract if you require further information.

Getting the APA format right for your abstract is important because it can impact your academic success.

Not complying with the APA format may affect your grades, or have your work published if that is your goal.

Let's dive into the step-by-step instructions on how to create your abstract page in APA format using Microsoft Word. I'll provide screenshots to make the process easier to follow.

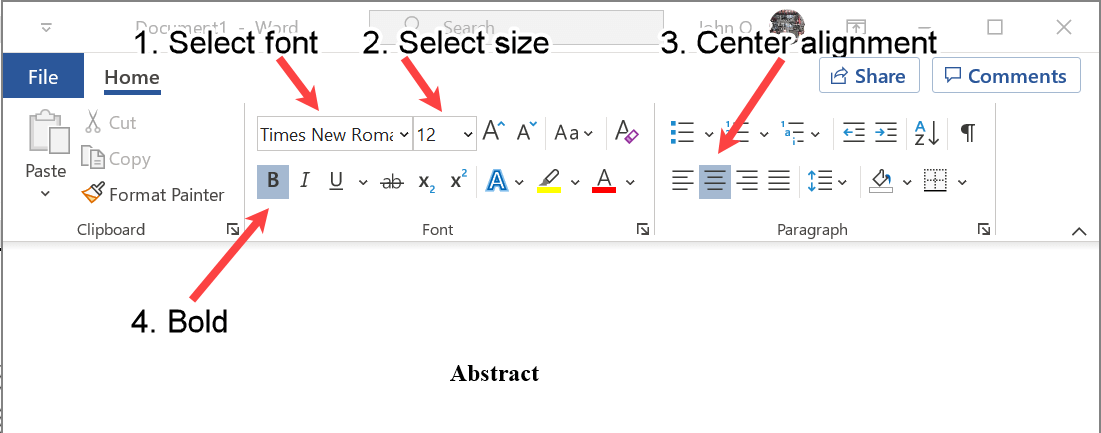

Heading for the Abstract Page

Step 1 - create the heading for the abstract paper in apa format.

According to APA seventh edition guidelines, different font types and sizes are recommended.

However, it's essential to use the same font type and size throughout your paper, including the title page, abstract, headings, subheadings, and paragraphs.

APA format requires you to have the heading "Abstract" (without quotes) on your abstract page.

The heading for your abstract page in APA format should be:

- use the same font type and size as the rest of your paper.

Figure 1 and the detailed instructions that follow show the font properties for the abstract label, using Times New Roman size 12 font as an example.

Figure 1 instructions (if required) are as follows:

- Select the text "Abstract".

- Select the Home tab.

- Choose your font type , such as Times New Roman.

- Select the appropriate font size , for example 12.

- Set the alignment to center .

- Set the Font style to Bold .

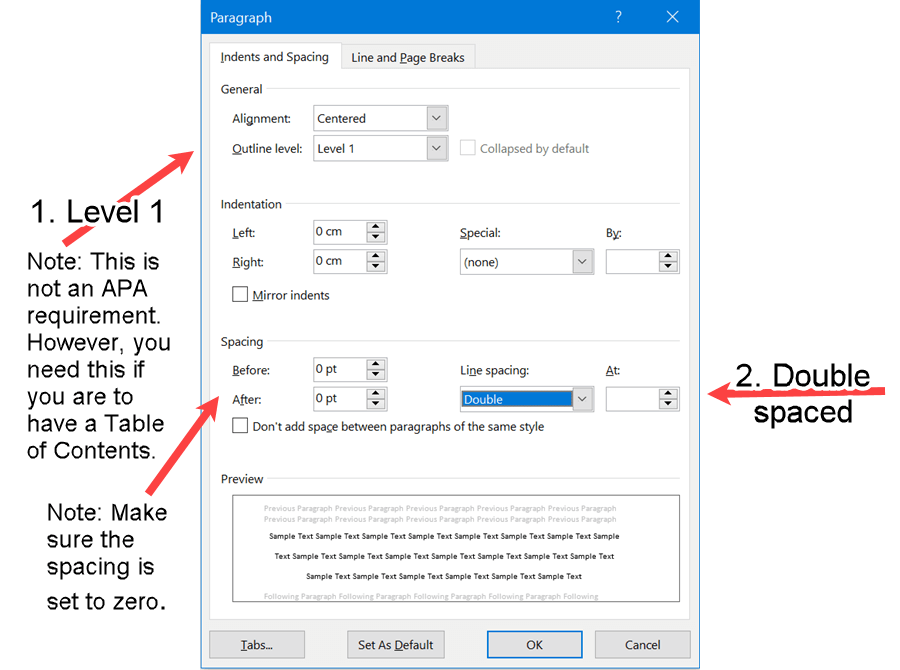

Step 2 - Set Outline Level and Line Spacing for the Heading

Instructions for Figure 2 (if needed) are:

- Select the arrow located at the bottom right-hand corner of the Paragraph group.

- If you're creating a Table of Contents, set the Outline level to Level 1 . Note that APA style does not specifically require a Table of Contents. However, if your instructor insists and you want the abstract heading to appear in the table of contents, then you should set the outline level to 1.

- Make sure the Before and After Spacing are set to zero . This is because you will be double spacing the lines in the next step.

- Set the Line spacing to Double . This will leave a blank line between the heading and the first line of the following paragraph.

- Click on OK to apply these settings.

By following these steps, you will format your abstract heading correctly, and it will be ready to use in your APA-style document.

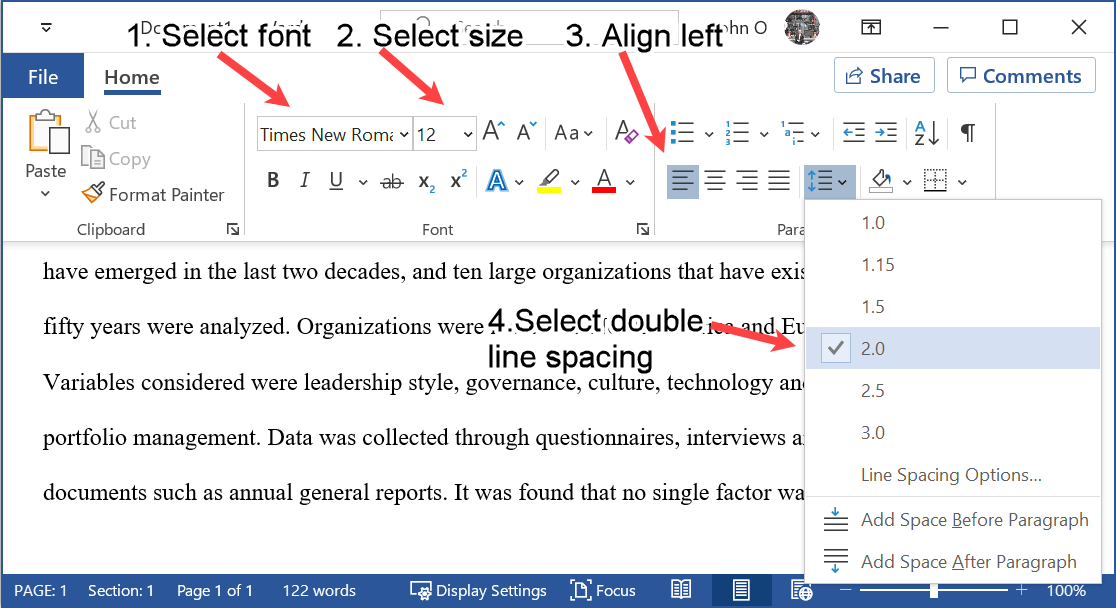

Abstract Paragraph

Figure 3 and the detailed instructions that follow demonstrate how to format the paragraph (or paragraphs) within an abstract in APA format.

Note: The first line is NOT indented. Paragraphs in the main text are, but not the abstract paragraph.

Instructions for Figure 3 (if needed) are:

- Select the Home tab at the top of the screen.

- Choose the font you have selected for your paper, for example "Times New Roman".

- Select the font size to the size you have chosen for your paper, for example size 12.

- Set the alignment to the left , so the text lines up on the left-hand side.

- Select Line and Paragraph Spacing and set it to 2.0 , which means the lines will be double-spaced.

By following these steps and using Figure 3 as a visual reference, you can correctly format the paragraphs in your abstract page in APA format.

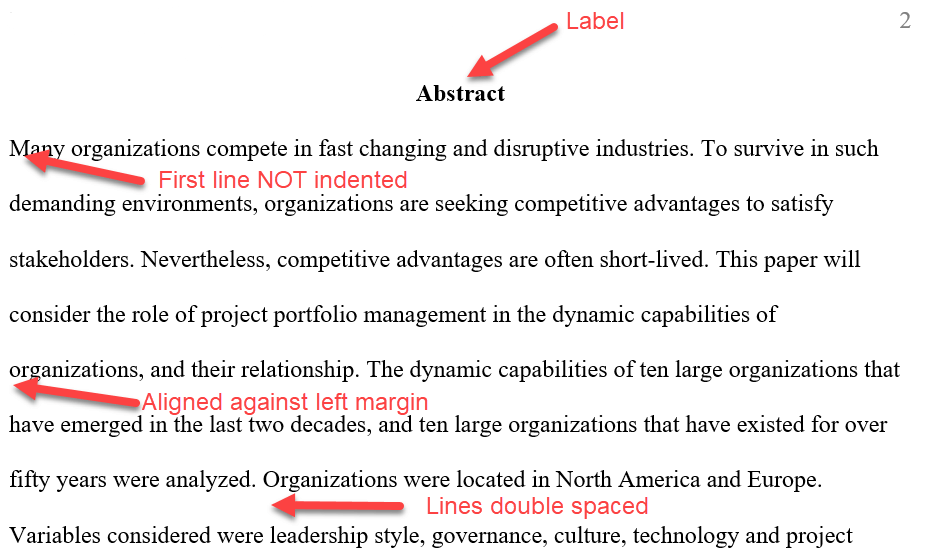

Example of an Abstract in APA Format

Figures 4 and 5 show an example of an abstract in APA format.

Figure 4 shows an abstract in a student paper.

Figure 5 shows an abstract in a professional paper.

What is the difference between a student paper and a professional paper?

A student paper is written for a course assignment whereas a professional paper is written for publication such as in a journal.

The only difference is that the professional paper (Figure 5) has the title (shortened if necessary) in the header.

Should You Use Microsoft Word Styles to Create the Abstract Page in APA Format?

Microsoft Word style refers to a predefined format for text, which includes aspects such as font type, font size, line spacing, bold, italic, and more.

Microsoft Word styles can be incredibly useful, as you only need to define the style once and then apply it consistently throughout your document.

You don't have to manually select the font, size, or formatting each time.

However, when it comes to writing abstracts, it is essential to consider how frequently you write them.

If you write only a few abstracts, you can follow the instructions provided in Figures 1 to 3 for formatting.

On the other hand, if you expect to write multiple abstracts during your academic writing career, it might be worthwhile to create a style for an abstract in APA format.

This will save you time and effort overall, as you can apply the predefined style consistently to all your abstracts.

Choose the option that suits your needs best, and you'll be on your way to creating well-formatted abstracts that meet the APA guidelines.

The abstract plays a significant role by giving readers a quick overview of your work and helping them decide if they want to read further.

The abstract is a summary of your entire paper, covering its main points, such as the purpose, methods, results, and conclusions. By following the step-by-step instructions, you can create a clear and well-structured abstract that adheres to APA guidelines.

Figures and written explanations for setting up the abstract heading, outline level, line spacing, and paragraph formatting have been provided. Properly formatting the abstract is essential for academic success, as it can impact your grades or determine if your work gets accepted for publication.

If you expect to write several abstracts in your academic career, consider creating a Microsoft Word style for consistent formatting, saving you time and effort.

By following these guidelines and examples, you'll be well-equipped to create professional and accurate abstracts in APA format.

References - APA Abstract

American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1037/0000165-000

Like This Page? Please Share It.

Note : The version of Microsoft Word used is the latest Word for Microsoft 365. The functions should also work in the 2021, 2019, 2016 and 2013 versions .

© Copyright www.apaword.com Privacy Policy About Me Microsoft Word screenshots used with permission from Microsoft. APA style has been developed and maintained by the American Psychological Association.

Magnum Proofreading Services

Writing an Abstract for a Research Paper: Guidelines, Examples, and Templates

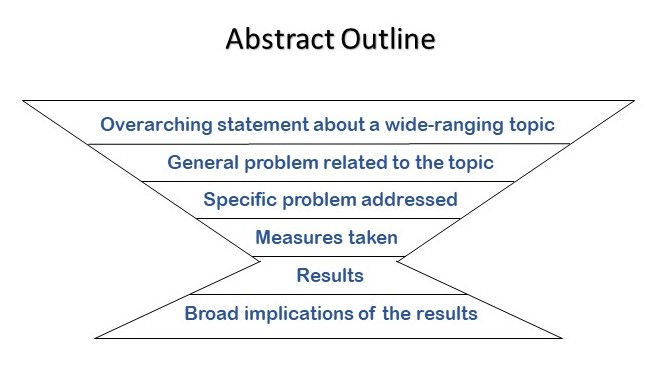

There are six steps to writing a standard abstract. (1) Begin with a broad statement about your topic. Then, (2) state the problem or knowledge gap related to this topic that your study explores. After that, (3) describe what specific aspect of this problem you investigated, and (4) briefly explain how you went about doing this. After that, (5) describe the most meaningful outcome(s) of your study. Finally, (6) close your abstract by explaining the broad implication(s) of your findings.

In this article, I present step-by-step guidelines for writing an abstract for an academic paper. These guidelines are fo llowed by an example of a full abstract that follows these guidelines and a few fill-in-the-blank templates that you can use to write your own abstract.

Guidelines for Writing an Abstract

The basic structure of an abstract is illustrated below.

A standard abstract starts with a very general statement and becomes more specific with each sentence that follows until once again making a broad statement about the study’s implications at the end. Altogether, a standard abstract has six functions, which are described in detail below.

Start by making a broad statement about your topic.

The first sentence of your abstract should briefly describe a problem that is of interest to your readers. When writing this first sentence, you should think about who comprises your target audience and use terms that will appeal to this audience. If your opening sentence is too broad, it might lose the attention of potential readers because they will not know if your study is relevant to them.

Too broad : Maintaining an ideal workplace environment has a positive effect on employees.

The sentence above is so broad that it will not grab the reader’s attention. While it gives the reader some idea of the area of study, it doesn’t provide any details about the author’s topic within their research area. This can be fixed by inserting some keywords related to the topic (these are underlined in the revised example below).

Improved : Keeping the workplace environment at an ideal temperature positively affects the overall health of employees.

The revised sentence is much better, as it expresses two points about the research topic—namely, (i) what aspect of workplace environment was studied, (ii) what aspect of employees was observed. The mention of these aspects of the research will draw the attention of readers who are interested in them.

Describe the general problem that your paper addresses.

After describing your topic in the first sentence, you can then explain what aspect of this topic has motivated your research. Often, authors use this part of the abstract to describe the research gap that they identified and aimed to fill. These types of sentences are often characterized by the use of words such as “however,” “although,” “despite,” and so on.

However, a comprehensive understanding of how different workplace bullying experiences are associated with absenteeism is currently lacking.

The above example is typical of a sentence describing the problem that a study intends to tackle. The author has noticed that there is a gap in the research, and they briefly explain this gap here.

Although it has been established that quantity and quality of sleep can affect different types of task performance and personal health, the interactions between sleep habits and workplace behaviors have received very little attention.

The example above illustrates a case in which the author has accomplished two tasks with one sentence. The first part of the sentence (up until the comma) mentions the general topic that the research fits into, while the second part (after the comma) describes the general problem that the research addresses.

Express the specific problem investigated in your paper.

After describing the general problem that motivated your research, the next sentence should express the specific aspect of the problem that you investigated. Sentences of this type are often indicated by the use of phrases like “the purpose of this research is to,” “this paper is intended to,” or “this work aims to.”

Uninformative : However, a comprehensive understanding of how different workplace bullying experiences are associated with absenteeism is currently lacking. The present article aimed to provide new insights into the relationship between workplace bullying and absenteeism .

The second sentence in the above example is a mere rewording of the first sentence. As such, it adds nothing to the abstract. The second sentence should be more specific than the preceding one.

Improved : However, a comprehensive understanding of how different workplace bullying experiences are associated with absenteeism is currently lacking. The present article aimed to define various subtypes of workplace bullying and determine which subtypes tend to lead to absenteeism .

The second sentence of this passage is much more informative than in the previous example. This sentence lets the reader know exactly what they can expect from the full research article.

Explain how you attempted to resolve your study’s specific problem.

In this part of your abstract, you should attempt to describe your study’s methodology in one or two sentences. As such, you must be sure to include only the most important information about your method. At the same time, you must also be careful not to be too vague.

Too vague : We conducted multiple tests to examine changes in various factors related to well-being.

This description of the methodology is too vague. Instead of merely mentioning “tests” and “factors,” the author should note which specific tests were run and which factors were assessed.

Improved : Using data from BHIP completers, we conducted multiple one-way multivariate analyses of variance and follow-up univariate t-tests to examine changes in physical and mental health, stress, energy levels, social satisfaction, self-efficacy, and quality of life.

This sentence is very well-written. It packs a lot of specific information about the method into a single sentence. Also, it does not describe more details than are needed for an abstract.

Briefly tell the reader what you found by carrying out your study.

This is the most important part of the abstract—the other sentences in the abstract are there to explain why this one is relevant. When writing this sentence, imagine that someone has asked you, “What did you find in your research?” and that you need to answer them in one or two sentences.

Too vague : Consistently poor sleepers had more health risks and medical conditions than consistently optimal sleepers.

This sentence is okay, but it would be helpful to let the reader know which health risks and medical conditions were related to poor sleeping habits.

Improved : Consistently poor sleepers were more likely than consistently optimal sleepers to suffer from chronic abdominal pain, and they were at a higher risk for diabetes and heart disease.

This sentence is better, as the specific health conditions are named.

Finally, describe the major implication(s) of your study.

Most abstracts end with a short sentence that explains the main takeaway(s) that you want your audience to gain from reading your paper. Often, this sentence is addressed to people in power (e.g., employers, policymakers), and it recommends a course of action that such people should take based on the results.

Too broad : Employers may wish to make use of strategies that increase employee health.

This sentence is too broad to be useful. It does not give employers a starting point to implement a change.

Improved : Employers may wish to incorporate sleep education initiatives as part of their overall health and wellness strategies.

This sentence is better than the original, as it provides employers with a starting point—specifically, it invites employers to look up information on sleep education programs.

Abstract Example

The abstract produced here is from a paper published in Electronic Commerce Research and Applications . I have made slight alterations to the abstract so that this example fits the guidelines given in this article.

(1) Gamification can strengthen enjoyment and productivity in the workplace. (2) Despite this, research on gamification in the work context is still limited. (3) In this study, we investigated the effect of gamification on the workplace enjoyment and productivity of employees by comparing employees with leadership responsibilities to those without leadership responsibilities. (4) Work-related tasks were gamified using the habit-tracking game Habitica, and data from 114 employees were gathered using an online survey. (5) The results illustrated that employees without leadership responsibilities used work gamification as a trigger for self-motivation, whereas employees with leadership responsibilities used it to improve their health. (6) Work gamification positively affected work enjoyment for both types of employees and positively affected productivity for employees with leadership responsibilities. (7) Our results underline the importance of taking work-related variables into account when researching work gamification.

In Sentence (1), the author makes a broad statement about their topic. Notice how the nouns used (“gamification,” “enjoyment,” “productivity”) are quite general while still indicating the focus of the paper. The author uses Sentence (2) to very briefly state the problem that the research will address.

In Sentence (3), the author explains what specific aspects of the problem mentioned in Sentence (2) will be explored in the present work. Notice that the mention of leadership responsibilities makes Sentence (3) more specific than Sentence (2). Sentence (4) gets even more specific, naming the specific tools used to gather data and the number of participants.

Sentences (5) and (6) are similar, with each sentence describing one of the study’s main findings. Then, suddenly, the scope of the abstract becomes quite broad again in Sentence (7), which mentions “work-related variables” instead of a specific variable and “researching” instead of a specific kind of research.

Abstract Templates

Copy and paste any of the paragraphs below into a word processor. Then insert the appropriate information to produce an abstract for your research paper.

Template #1

Researchers have established that [Make a broad statement about your area of research.] . However, [Describe the knowledge gap that your paper addresses.] . The goal of this paper is to [Describe the purpose of your paper.] . The achieve this goal, we [Briefly explain your methodology.] . We found that [Indicate the main finding(s) of your study; you may need two sentences to do this.] . [Provide a broad implication of your results.] .

Template #2

It is well-understood that [Make a broad statement about your area of research.] . Despite this, [Describe the knowledge gap that your paper addresses.] . The current research aims to [Describe the purpose of your paper.] . To accomplish this, we [Briefly explain your methodology.] . It was discovered that [Indicate the main finding(s) of your study; you may need two sentences to do this.] . [Provide a broad implication of your results.] .

Template #3

Extensive research indicates that [Make a broad statement about your area of research.] . Nevertheless, [Describe the knowledge gap that your paper addresses.] . The present work is intended to [Describe the purpose of your paper.] . To this end, we [Briefly explain your methodology.] . The results revealed that [Indicate the main finding(s) of your study; you may need two sentences to do this.] . [Provide a broad implication of your results.] .

- How to Write an Abstract

Related Posts

How to Write a Research Paper in English: A Guide for Non-native Speakers

How to Write an Abstract Quickly

Using the Present Tense and Past Tense When Writing an Abstract

Well explained! I have given you a credit

APA Style (7th ed.)

- Cite: Why? When?

- Book, eBook, Dissertation

- Article or Report

- Business Sources

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) Tools

- In-Text Citation

- Format Your Paper

Format Your Paper

Download and use the editable templates for student papers below: .

- APA 7th ed. Template Document This is an APA format template document in Google Docs. Click on the link -- it will ask for you to make a new copy of the document, which you can save in your own Google Drive with your preferred privacy settings.

- APA 7th ed. Template Document A Microsoft Word document formatted correctly according to APA 7th edition.

- APA 7th ed. Annotated Bibliography template A Microsoft Word document formatted correctly for an annotated bibliography.

Or, view the directions for specific sections below:

Order of sections (section 2.17).

- Title page including Title, Author, University and Department, Class, Instructor, and Date

- Body (including introduction, literature review or background, discussion, and conclusion)

- Appendices (including tables & figures)

Margins & Page Numbers (sections 2.22-2.24)

- 1 inch at top, bottom, and both sides

- Left aligned paragraphs and leave the right edge ragged (not "right justified")

- Indent first line of each paragraph 1/2 inch from left margin

- Use page numbers, including on the title page, 1/2 inch from top and flush with right margin

Text Format (section 2.19)

- Times New Roman, 12 point

- Calibri, 11 point

- Arial, 11 point

- Lucinda Sans Unicode, 10 point

- Georgia, 11 point

- Double-space and align text to the left

- Use active voice

- Don't overuse technical jargon

- No periods after a web address or DOI in the References list.

Tables and Figures In-Text (chapter 7)

- Label tables and figures numerically (ex. Table 1)

- Give each table column a heading and use separating lines only when necessary

- Design the table and figure so that it can be understood on its own, i.e. it does not require reference to the surrounding text to understand it

- Notes go below tables and figures

Title Page (section 2.3)

- Include the title, your name, the class name , and the college's name

- Title should be 12 words or less and summarize the paper's main idea

- No periods or abbreviations

- Do not italicize or underline

- No quotation marks, all capital letters, or bold

- Center horizontally in upper half of the page

Body (section 2.11)

- Align the text to the left with a 1/2-inch left indent on the first line

- Double-space

- As long as there is no Abstract, at the top of the first page, type the title of the paper, centered, in bold , and in Sentence Case Capitalization

- Usually, include sections like these: introduction, literature review or background, discussion, and conclusion -- but the specific organization will depend on the paper type

- Spell out long organization names and add the abbreviation in parenthesis, then just use the abbreviation

- Spell out numbers one through nine and use a number for 10 or more

- Use a number for units of measurement, in tables, to represent statistical or math functions, and dates or times

Headings (section 2.26-2.27)

- Level 1: Center, bold , Title Case

- Level 2: Align left, bold , Title Case

- Level 3: Alight left, bold italics , Title Case

- Level 4: Indented 1/2", bold , Title Case, end with a period. Follow with text.

- Level 5: Indented 1/2", bold italics , Title Case, end with a period. Follow with text.

Quotations (sections 8.26-8.33)

- Include short quotations (40 words or less) in-text with quotation marks

- For quotes more than 40 words, indent the entire quote a half inch from the left margin and double-space it with no quotation marks

- When quoting two or more paragraphs from an original source, indent the first line of each paragraph a half inch from the left margin

- Use ellipsis (...) when omitting sections from a quote and use four periods (....) if omitting the end section of a quote

References (section 2.12)

Begins on a new page following the text of your paper and includes complete citations for the resources you've used in your writing.

- References should be centered and bolded at the top of a new page

- Double-space and use hanging indents (where the first line is on the left margin and the following lines are indented a half inch from the left)

- List authors' last name first followed by the first and middle initials (ex. Skinner, B. F.)

- Alphabetize the list by the first author's last name of of each citation (see sections 9.44-9.49)

- Capitalize only the first word, the first after a colon or em dash, and proper nouns

- Don't capitalize the second word of a hyphenated compound

- No quotation marks around titles of articles

Appendices with Tables, Figures, & Illustrations (section 2.14, and chapter 7)

- Include appendices only to help the reader understand, evaluate, or replicate the study or argument

- Put each appendix on a separate page and align left

- For text, do not indent the first paragraph, but do indent the rest

- If you have only one appendix, label it "Appendix"

- If you have two or more appendices, label them "Appendix A", "Appendix B" and so forth as they appear in the body of your paper

- Label tables and figures numerically (ex. Table 1, or Table B1 and Table B2 if Appendix B has two tables) and describe them within the text of the appendix

- Notes go below tables and figures (see samples on p. 210-226)

Annotated Bibliography

Double-space the entire bibliography. give each entry a hanging indent. in the following annotation, indent the entire paragraph a half inch from the left margin and give the first line of each paragraph a half inch indent. see the template document at the top of this page..

- Check with your professor for the length of the annotation and which elements you should evaluate.

These elements are optional, if your professor or field requires them, but they are not required for student papers:

Abstract (section 2.9).

- Abstract gets its own page

- Center "Abstract" heading and do not indent the first line of the text

- Summarize the main points and purpose of the paper in 150-250 words maximum

- Define abbreviations and acronyms used in the paper

Running Head (section 2.8 )

- Shorten title to 50 characters or less (counting spaces and punctuation) for the running head

- In the top margin, the running head is aligned left, with the page number aligned on the right

- On every page, put (without the brackets): [SHORTENED TITLE OF YOUR PAPER IN ALL CAPS] [page number]

More questions? Check out the authoritative source: APA style blog

- << Previous: In-Text Citation

- Last Updated: Aug 19, 2024 4:18 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uww.edu/apa

Work With Us

Private Coaching

Done-For-You

Short Courses

Client Reviews

Free Resources

Free Download

Research Paper Template

The fastest (and smartest) way to craft a research paper that showcases your project and earns you marks.

Available in Google Doc, Word & PDF format 4.9 star rating, 5000 + downloads

Step-by-step instructions

Tried & tested academic format

Fill-in-the-blanks simplicity

Pro tips, tricks and resources

What It Covers

This template’s structure is based on the tried and trusted best-practice format for academic research papers. Its structure reflects the overall research process, ensuring your paper has a smooth, logical flow from chapter to chapter. Here’s what’s included:

- The title page/cover page

- Abstract (or executive summary)

- Section 1: Introduction

- Section 2: Literature review

- Section 3: Methodology

- Section 4: Findings /results

- Section 5: Discussion

- Section 6: Conclusion

- Reference list

Each section is explained in plain, straightforward language , followed by an overview of the key elements that you need to cover within each section.

You can download a fully editable MS Word File (DOCX format), copy it to your Google Drive or paste the content to any other word processor.

download your copy

100% Free to use. Instant access.

I agree to receive the free template and other useful resources.

Download Now (Instant Access)

FAQs: Research Paper Template

What format is the template (doc, pdf, ppt, etc.).

The research paper template is provided as a Google Doc. You can download it in MS Word format or make a copy to your Google Drive. You’re also welcome to convert it to whatever format works best for you, such as LaTeX or PDF.

What types of research papers can this template be used for?

The template follows the standard best-practice structure for formal academic research papers, so it is suitable for the vast majority of degrees, particularly those within the sciences.

Some universities may have some additional requirements, but these are typically minor, with the core structure remaining the same. Therefore, it’s always a good idea to double-check your university’s requirements before you finalise your structure.

Is this template for an undergrad, Masters or PhD-level research paper?

This template can be used for a research paper at any level of study. It may be slight overkill for an undergraduate-level study, but it certainly won’t be missing anything.

How long should my research paper be?

This depends entirely on your university’s specific requirements, so it’s best to check with them. We include generic word count ranges for each section within the template, but these are purely indicative.

What about the research proposal?

If you’re still working on your research proposal, we’ve got a template for that here .

We’ve also got loads of proposal-related guides and videos over on the Grad Coach blog .

How do I write a literature review?

We have a wealth of free resources on the Grad Coach Blog that unpack how to write a literature review from scratch. You can check out the literature review section of the blog here.

How do I create a research methodology?

We have a wealth of free resources on the Grad Coach Blog that unpack research methodology, both qualitative and quantitative. You can check out the methodology section of the blog here.

Can I share this research paper template with my friends/colleagues?

Yes, you’re welcome to share this template. If you want to post about it on your blog or social media, all we ask is that you reference this page as your source.

Can Grad Coach help me with my research paper?

Within the template, you’ll find plain-language explanations of each section, which should give you a fair amount of guidance. However, you’re also welcome to consider our private coaching services .

Additional Resources

If you’re working on a research paper or report, be sure to also check these resources out…

1-On-1 Private Coaching

The Grad Coach Resource Center

The Grad Coach YouTube Channel

The Grad Coach Podcast

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Definition and Purpose of Abstracts An abstract is a short summary of your (published or unpublished) research paper, usually about a paragraph (c. 6-7 sentences, 150-250 words) long. A well-written abstract serves multiple purposes: an abstract lets readers get the gist or essence of your paper or article quickly, in order to decide whether to…

APA 7th ed. Fillable Word Template and Sample Paper. APA 7th ed. Template. Download this Word document, fill out the title page and get writing! ... Our APA sample paper shows you how to format the main parts of a basic research paper. APA 7th Sample Papers from Purdue Owl << Previous: Block Quotations; Next: Government Documents and Legal ...

The abstract should focus on your original research, not on the work of others. The abstract should be self-contained and fully understandable without reference to other sources. There are some circumstances where you might need to mention other sources in an abstract: for example, if your research responds directly to another study or focuses ...

Follow these five steps to format your abstract in APA Style: Insert a running head (for a professional paper—not needed for a student paper) and page number. Set page margins to 1 inch (2.54 cm). Write "Abstract" (bold and centered) at the top of the page. Place the contents of your abstract on the next line. Do not indent the first line.

Abstract Page in APA Format: How to Write Using Microsoft Word. This guide shows you how to create an abstract page in APA format using Microsoft Word. The abstract plays a crucial role in your academic paper—whether you're working on a research paper, thesis, review, case study, report, or essay.

There are six steps to writing a standard abstract. (1) Begin with a broad statement about your topic. Then, (2) state the problem or knowledge gap related to this topic that your study explores. After that, (3) describe what specific aspect of this problem you investigated, and (4) briefly explain how you went about doing this. After that, (5) describe the most meaningful outcome(s) of your ...

determine whether to include an abstract and/or keywords. ABSTRACT: The abstract needs to provide a brief but comprehensive summary of the contents of your paper. It provides an overview of the paper and helps readers decide whether to read the full text. Limit your abstract to 250 words. 1. Abstract Content . The abstract addresses the following

These sample papers demonstrate APA Style formatting standards for different student paper types. Students may write the same types of papers as professional authors (e.g., quantitative studies, literature reviews) or other types of papers for course assignments (e.g., reaction or response papers, annotated bibliographies, discussion posts), dissertations, and theses.

Body (section 2.11) Align the text to the left with a 1/2-inch left indent on the first line; Double-space; As long as there is no Abstract, at the top of the first page, type the title of the paper, centered, in bold, and in Sentence Case Capitalization; Usually, include sections like these: introduction, literature review or background, discussion, and conclusion -- but the specific ...

This template's structure is based on the tried and trusted best-practice format for academic research papers. Its structure reflects the overall research process, ensuring your paper has a smooth, logical flow from chapter to chapter. Here's what's included: The title page/cover page; Abstract (or executive summary) Section 1: Introduction